– “How many riders got off the bike because they couldn’t stand the friction with the saddle anymore?,” asks Pedro Delgado.

It certainly happened more often in the days of leather chamois, which were rough and creased.

With the cumulative stress of hours and days and weeks of riding, with sweat and dust, rough and bumpy roads, any imperfection in the chamois could leave a rider in severe pain.

The friction produced boils, abscesses, fistulas. And the riders endured a martyrdom that often ended in abandonment.

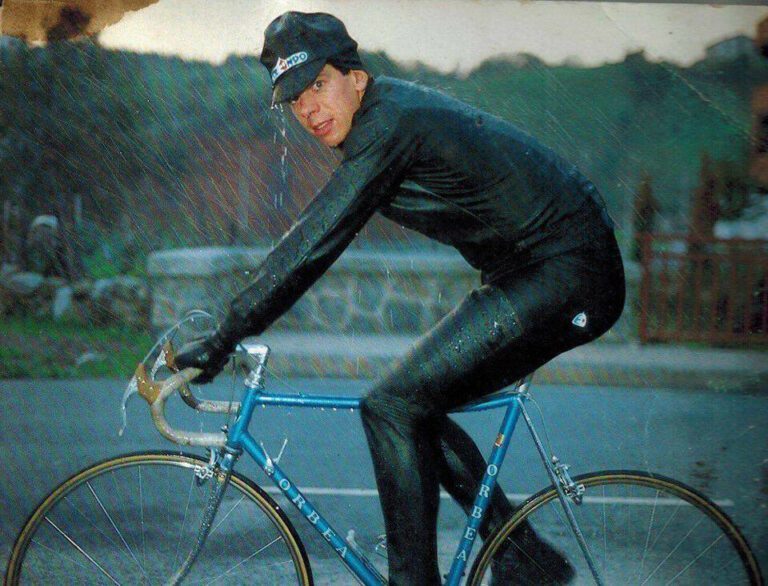

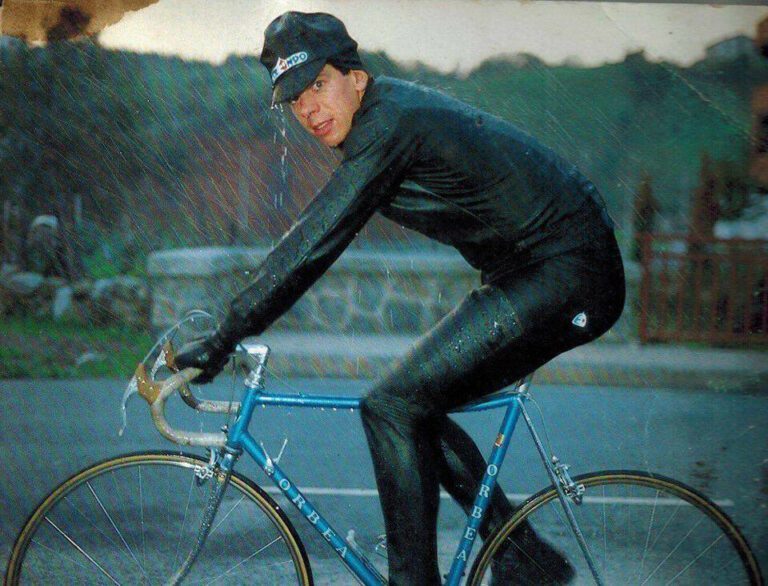

– “I had some problems of that type when I was younger, but by the 1980s we were already turning the page,” Delgado continues over the phone. “Etxeondo came in as our clothing sponsor and everything changed.

“Paco’s obsession was with shorts and chamois, he was always looking for ways to improve them; we switched to lycra shorts and synthetic chamois and I no longer had any problems.

“But in previous times…wow, the veterans will tell you the horror stories about the steaks that were put on to treat chafing.”

The veterans are Txomin Perurena and Ramón Mendiburu, who sat down with Paco Rodrigo, the founder of Etxeondo, to discuss the modernization of cycling in general and clothing in particular during the 1980s. Paco begins by pointing out:

– We continue to call them chamois, but now they are no longer chamois.

The dictionary confirms it: chamois is a tanned sheepskin. Strips of this leather were sewn inside hats to absorb sweat. They were also used as cushioning for horseback riding. From there, they moved into cycling.

– “The finest was the caloyo: newborn lamb. The skin of the lamb that had not gone out into the field, that had not even received sunlight, was sought. It wasn’t any better than today’s synthetics, but it was very soft, very nice, the finest there was, and it cost a fortune.

“I have always been interested in textures, they are my obsession. “And I saw that in the shorts they often used lamb skins that had already gone out into the fields, sheep skins, harder skins.

“Sometimes they had tiny vegetable thorns embedded in them.

“They were rough, itchy, with the little spikes on the leather; you can imagine what happened to the rider”.

Delgado belongs to a former generation, one that grew up with the bottle of moisturising cream always in their suitcase.

-Until the synthetic pads arrived, chamois were always a preoccupation for every rider. You had to feed them with cream so they wouldn’t get hard, but not so much cream it would form a thick paste. So what cream do you put on it and how much do you put on it….

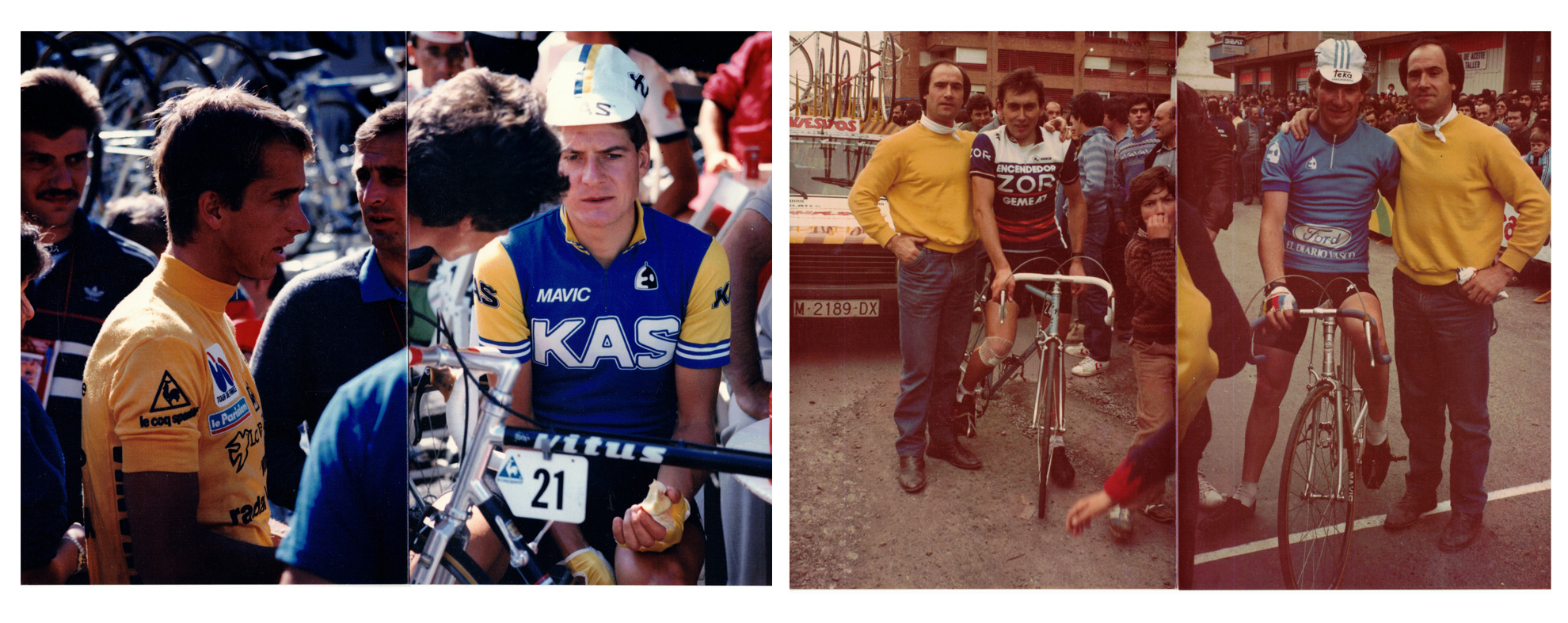

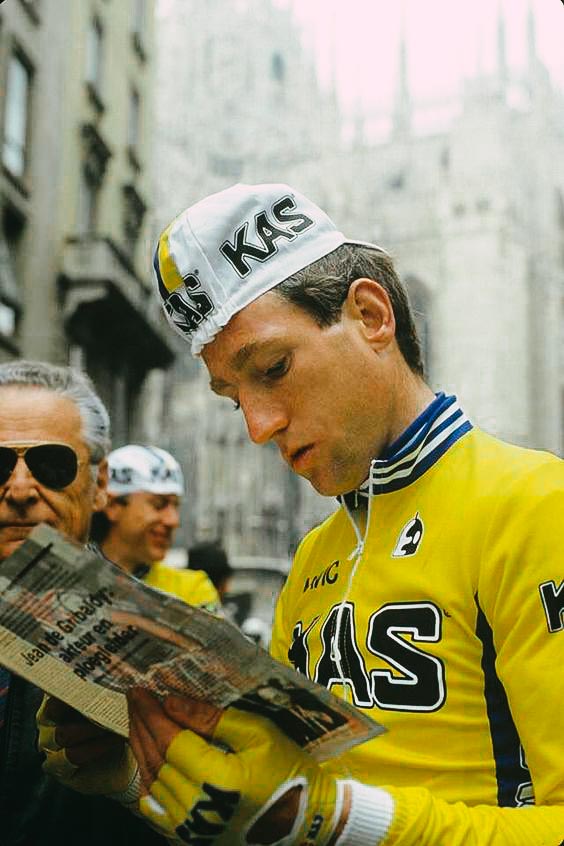

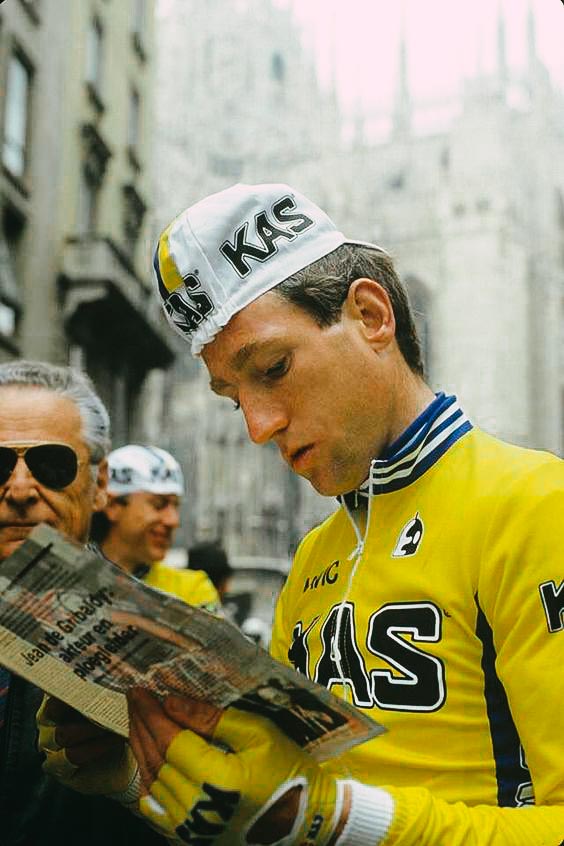

Perurena, the winner of 158 races between 1966 and 1979 with Fagor, Kas and Teka, recalls an era when riders had a sparse selection of clothing on race day.

-“We were going for a three week race with two or three pairs of shorts, nothing more,” he says.“At the end of each stage we washed the shorts in the hotel sink with a bar of soap.“But we didn’t always do it; after taking a beating all day we didn’t feel like washing, and sometimes we used the same shorts the next day. “We did not care about hygiene.”

“That’s very bad,” Paco interjects. “The shorts must be washed after each use, even if you have only done 20 kilometres, because if you leave them sweaty, bacteria multiply, the chamois is damaged and you are damaged.

“That’s where the infections come from.”

Delgado belongs to a former generation, one that grew up with the bottle of moisturising cream always in their suitcase.

Until the synthetic pads arrived, chamois were always a preoccupation for every rider.

You had to feed them with cream so they wouldn’t get hard, but not so much cream it would form a thick paste. So what cream do you put on it and how much do you put on it….

Perurena, the winner of 158 races between 1966 and 1979 with Fagor, Kas and Teka, recalls an era when riders had a sparse selection of clothing on race day.

“We were going for a three week race with two or three pairs of shorts, nothing more,” he says.

“At the end of each stage we washed the shorts in the hotel sink with a bar of soap.

“But we didn’t always do it; after taking a beating all day we didn’t feel like washing, and sometimes we used the same shorts the next day.

“We did not care about hygiene.”

“That’s very bad,” Paco interjects. “The shorts must be washed after each use, even if you have only done 20 kilometres, because if you leave them sweaty, bacteria multiply, the chamois is damaged and you are damaged.

“That’s where the infections come from.”

Mendiburu, a rider in the 1960s, national coach, director of the Vuelta a España and the International Cycling Union, and manager of the Kas and Fagor teams, recalls one of his worst moments on the saddle.

– “In the 1967 Tour I had a terrible time with furunculosis,” he remembers. “I got several boils and other teammates did too, an epidemic. I couldn’t even sit down. And they gave me a fever.”

Boils are inflammations caused by a bacterial infection, they usually occur in areas of the body with hair, moisture and friction with clothing.

– “I retired in the Pyrenees, almost at the end of the Tour,” says Mendiburu. I returned to San Sebastián and was treated by Dr. Echavarren”, a specialist in sports medicine.“He saw how it was all red, all inflamed, and he asked me: ‘How do you ride like that? It can give you a terrible infection”.“He drew blood from my arm, injected it into that area, and it healed right away.”

To add to the rough leather, the lack of hygiene and the dust on the roads, there was the infernal heat of that 1967 Tour.

-“On the way out of Marseilles it was incredibly hot,” says Mendiburu.

“I will never forget seeing Tom Simpson scooping up water from a ditch with his cap and pouring it over his head. “I thought: ‘If you’re already roasted now, how will you be in 200 kilometres….’.”

Mid-race, Jesús Aranzábal stopped and put his head in a water trough, he came out with all the scum hanging from his ears… and two bottles of Champagne that someone had left there to cool.

Then, after 200 kilometres, Mont Ventoux loomed…

-“I went up in a small group with Jean Stablinski,” says Mendiburu.

“With a couple of kilometres to go, on that exposed, stony mountain, we saw a group of people in the gutter, around a cyclist lying on the ground.

“Dr. Dumas was giving him mouth-to-mouth.“Stablinski asked: “Qui est-ce?” “C’est Tom, c’est Tom!”

“I ALWAYS HAD AMBITIOUS PEOPLE CLOSE TO ME”.

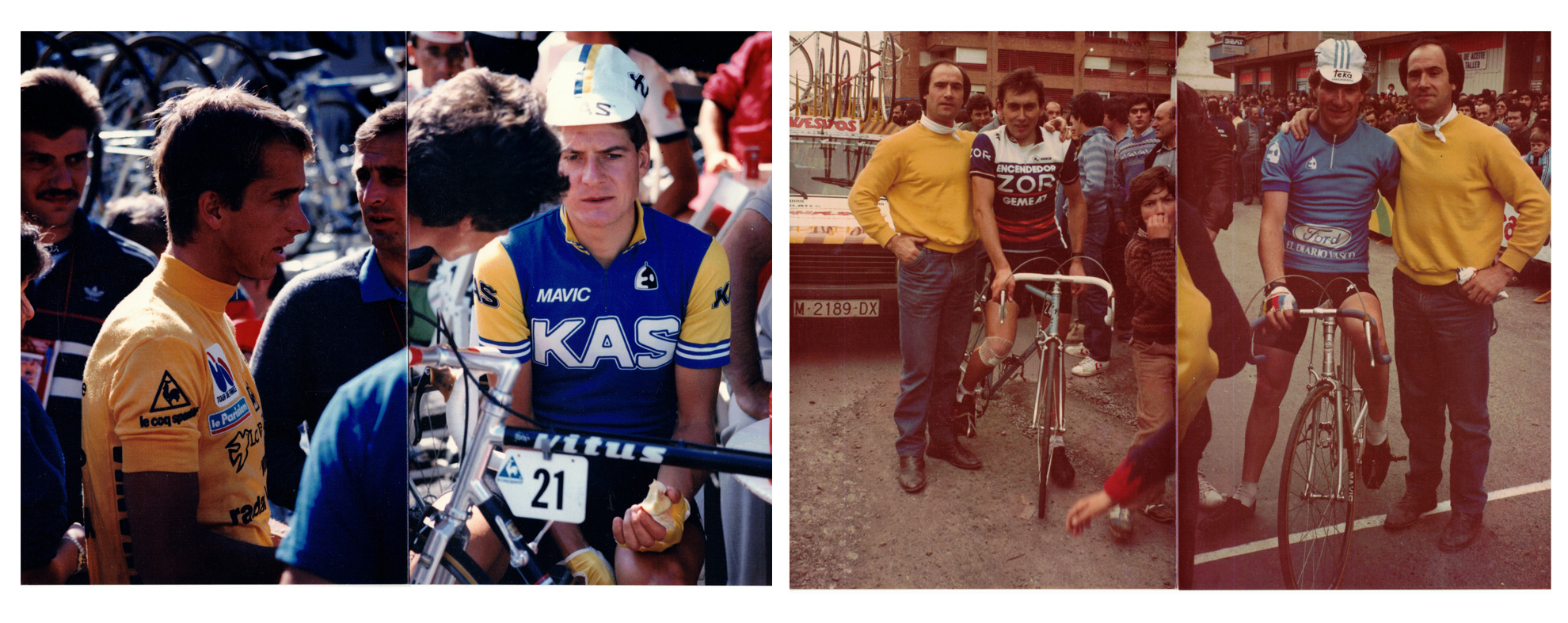

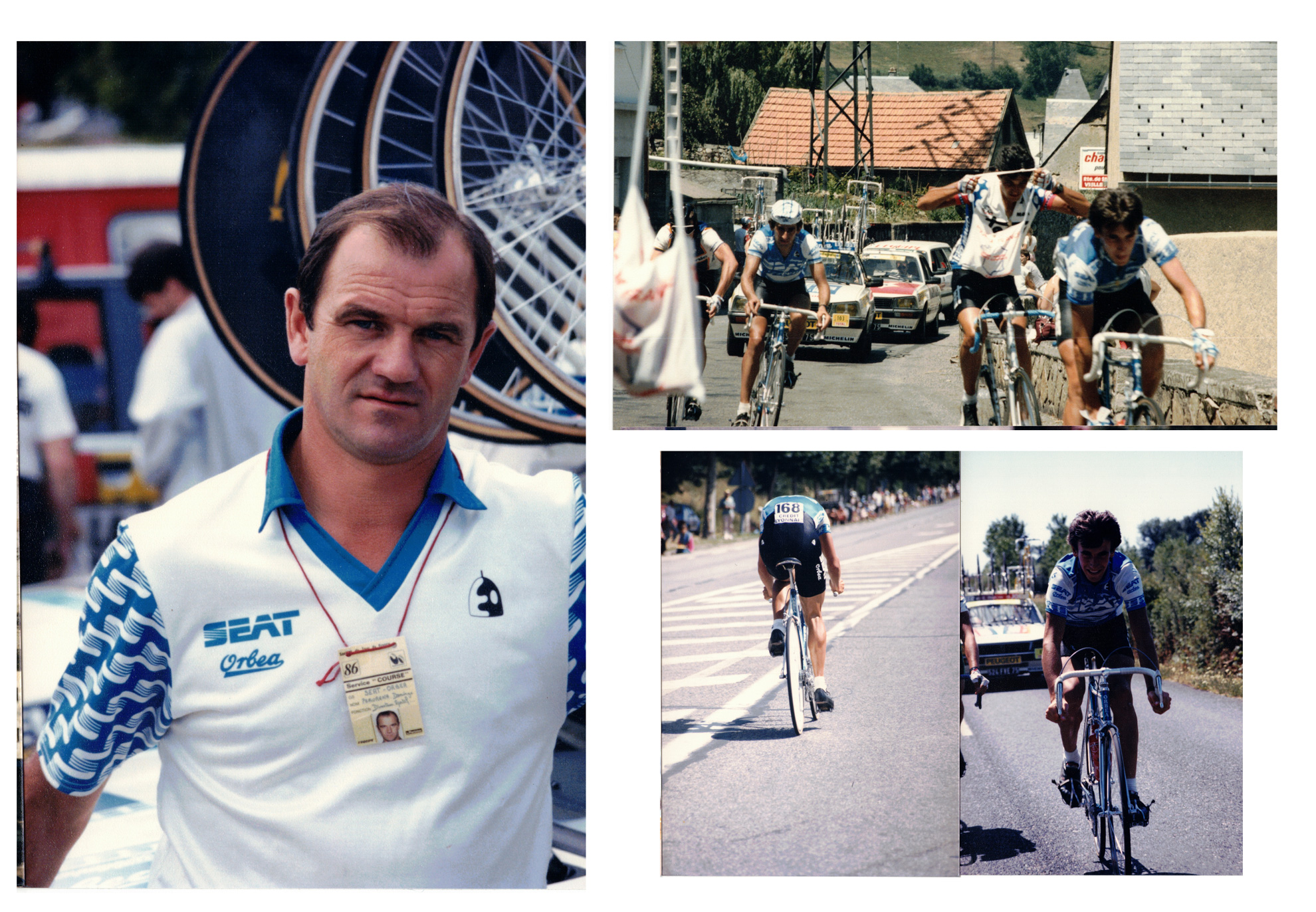

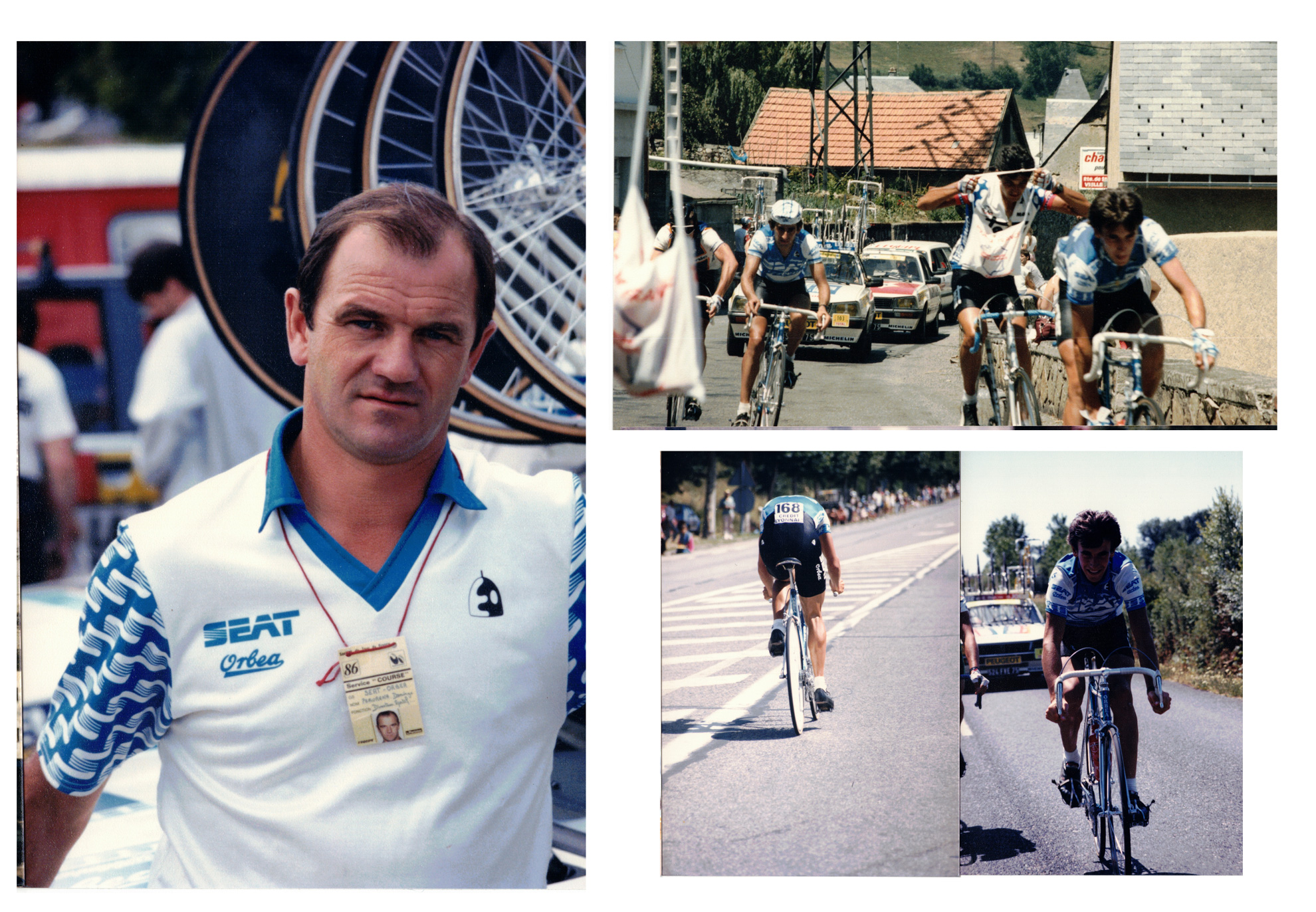

In the early 1980s, Spanish cycling was modernising rapidly. Television broadcast the Vuelta live for the first time, the press and the radio devoted a lot of space and time to cycling, and that visibility attracted more sponsors, so budgets increased and equipment improved.

Mendiburu, technical director of the Vuelta a España, was at the centre of the transformation.

-“Spanish television had only been giving a summary of the racing for 20 minutes each evening,” he says.“At the end of the 1982 Vuelta they told us: ‘Next year, if you bring Bernard Hinault, we will show the race live.’ “I went to Paris to ask Félix Lévitan, organiser of the Tour, to lend me a hand.“He convinced Cyrille Guimard, the director of Hinault, and told me that it was already done, to talk to him to agree on the conditions. “We brought Hinault to the race, it was the first Vuelta broadcast live and it turned out to be phenomenal: a battle between Hinault and Lejarreta, Gorospe, Alberto Fernández, the first finish at the Enol Lakes.“Hinault won but it cost him his knee injury. He had to have surgery, and missed the Tour.” “From then on, everything changed very fast,” says Paco Rodrigo. “In the same 1983 season, Etxeondo equipped its first professional riders and saw them climb to the podiums of the Giro and the Tour.“We came from printing shirts in our little village, from dressing the Orbea-Danena amateur team, and suddenly we were in the front row of world cycling.“Sometimes it felt like events were ahead of us; we achieved more success than expected and from our small workshop we had to go to fairs all over Europe and compete with the best in cycling clothing. “I didn’t feel dizzy, I just felt a lot of energy.

“Zor and Reynolds gave us visibility, we sold a lot of clothing, it was a financial boost and I saw Etxeondo was gaining prestige, that we could compete.“Look what great riders we had: Alberto Fernández, Chozas, Pino, Gorospe, Arroyo, Delgado.“It was a generation that shook off its inferiority complex. We did the same.”

At that time, Delgado was only 23 years old. He made his debut in the Tour, dazzled with three second places in high mountains and stayed close to Laurent Fignon’s yellow jersey until he slipped away in the final week.

-“We went to the Tour because José Miguel Echavarri insisted” -says Delgado-.

The Spanish teams hardly went abroad in those days because in Spain there were races all year round and they had no need or desire to compete in other countries. But Echavarri was a young and ambitious director, he asked for a place on the Tour and off we went, feeling self-conscious. “In the first stages, we were shocked at the speed. It was crazy, we were scared.“Every time there was a crash in the peloton they yelled at us Spaniards and Colombians: ‘You don’t know how to ride’. “We were second class cyclists. “During the first week, reaching the finish line was already a triumph. “But in the mountains, everything changed.

“Arroyo won the Puy-de-Dôme time trial, I was second, and at night, having dinner at the hotel, Peter Post, director of Ti Raleigh, the great Dutch team, came to congratulate us. I didn’t give it much importance. But Echavarri told us: ‘Hey, have you seen who congratulated us? We have earned the respect of the peloton’.”

Delgado suddenly found himself fighting to win the Tour.

-“We changed our mentality quickly,” he remembers. “Until then, we thought we were at a disadvantage: the French, the Belgians or the Dutch had better bikes, better kit, more professional teams. “In reality, we found there was not much difference so we shook that complex off right away”.

One of the advances that Delgado remembers is that of clothing.

-“Etxeondo arrived and finally we had a jersey and not a blanket,” he laughs.

“Until then we wore coarser wool jerseys, loose fitting, which were hot in summer and became heavy in the rain. The appearance of lycra greatly improved everything”.

-Paco was so meticulous; he gave us a light jersey for hot days and a thicker one for cold days. That was big news. We were the envy of the bunch: we had those lycra shorts that shone, skin-tight time trial suits, the headbands to keep sweat out of your eyes. We had clothes that fitted us well.

Delgado remembers Paco Rodrigo often spoke with the riders to ask for their feedback.

-In the first lycra shorts, for example, the chamois cracked and came loose right away. We told him: ‘See, Paco, a disaster’ and he went away and solved the problem.He was always obsessed with evolving. We were all young, the directors, the riders, the clothing. We all learned hand in hand.

-We grew up together, yes, -confirms Paco-. Trial and error, changing some things for others, that’s how we learned.Back then there were no digital technologies or biomechanical studies or anything so precise. Our work had a romantic touch, of intuition, of creativity, of the craftsman’s experience. I was passionate about that. I put in a lot of hours, a lot.The good thing is that I always had ambitious people around me and they inspired me. Peli Egaña and Patxi Alkorta, who set up the Orbea team, put a lot of pressure on me, they demanded that I compete with the best.

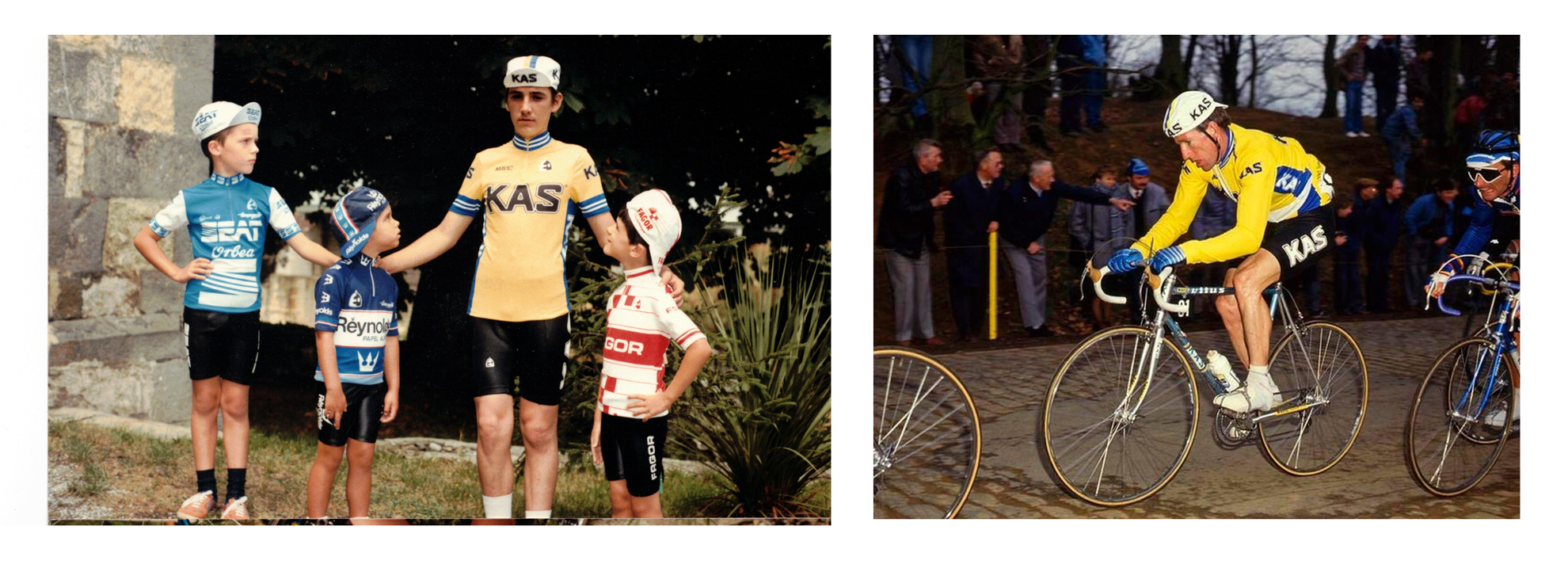

The Orbea amateur team, led by young riders Pello Ruiz Cabestany and Jokin Mujika, turned professional en bloc in 1984. Etxeondo had already been a sponsor for five years and stayed with them as they set about establishing their place in the international peloton.

They had hired Txomin Perurena as sports director.

-“Txomin knew everyone,” Paco Rodrigo continues. “Sometimes we met with important people, sponsors, heads of companies, and when we got to the places, he would get behind and push me a little ‘Come on, Navarrese, push forward.’“He wanted them to get to know me, for me to tell them about Etxeondo. “One day we went to a fair, I don’t know where, in Germany or France…”

-In Milan -corrects Perurena-. We went to a fair to see clothes and then to a factory.

-Ah, yes, we went to the factory,” says Paco. “Some textile engineers greeted us, they asked me what we were looking for and I told them: ‘Elastomers’.

Perurena laughs:

-I was impressed. Fucked with Paco! elastomers!

-Man, you wondered where the Navarrese was going, and then you saw that he understood the engineers from Milan, that he spoke the same language.

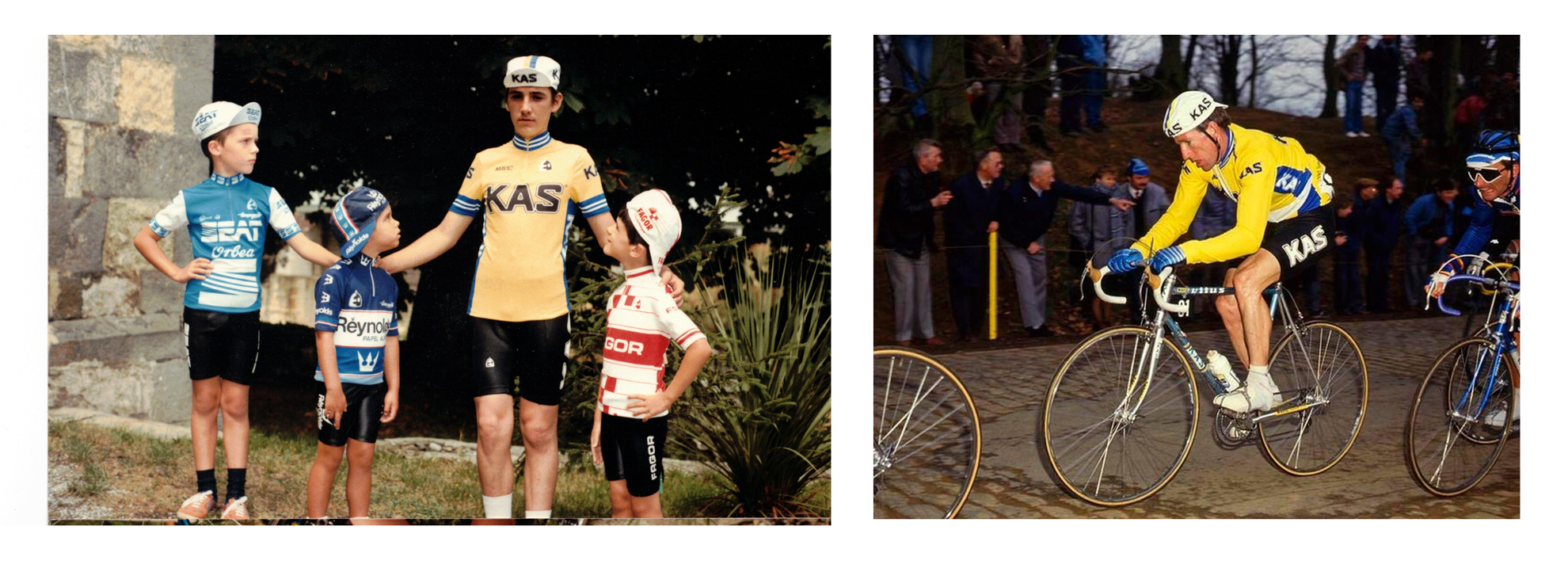

Orbea grew fast. Cabestany won the Tour of the Basque Country in 1985 and triggered an explosion in popularity: the home kid, riding for the home team, dressed in home kit, won the home race against figures like Lemond, Kelly and Delgado. The same year, Cabestany wore yellow for several days in the Vuelta a España and won a stage. The following season, he won a stage in the Tour. Sponsorships such as Gin MG, Seat and then Caja Rural provided the funding for signings like Delgado, who, in 1985, finished off a legendary stage for Orbea at Luz Ardiden.

Paco Rodrigo travelled in the team cars during that Tour and on one occasion, found himself in the spotlight.

-Paco Rodrigo travelled in the team cars during that Tour and on one occasion, found himself in the spotlight. A few days before arriving in the Pyrenees, in the middle of Sanfermines, some Colombian journalists from Radio Caracol approached the window of the first car:

“We have Don Domingoooo Perurenaaa, a legendary cyclist, director of the Orrrrbeaaaa team…”

Perurena answered a couple of questions and changed the subject:

-“Also in the car is Paco Rodrigo, ‘El Ruiseñor de las Bardenas’, a great Navarrese singer of jotas. Paco, sing something to our Colombian friends, come on.

-“Live with you, for all of Colombia, the jotas singer Don Paco Rodrigoooo!”

Paco bursts out laughing:

-“I sang them the jot of tears: ‘Shoot me, pretty girl / tears in my handkerchief / and I’ll take them to Pamplona / let a silversmith crimp them’.”

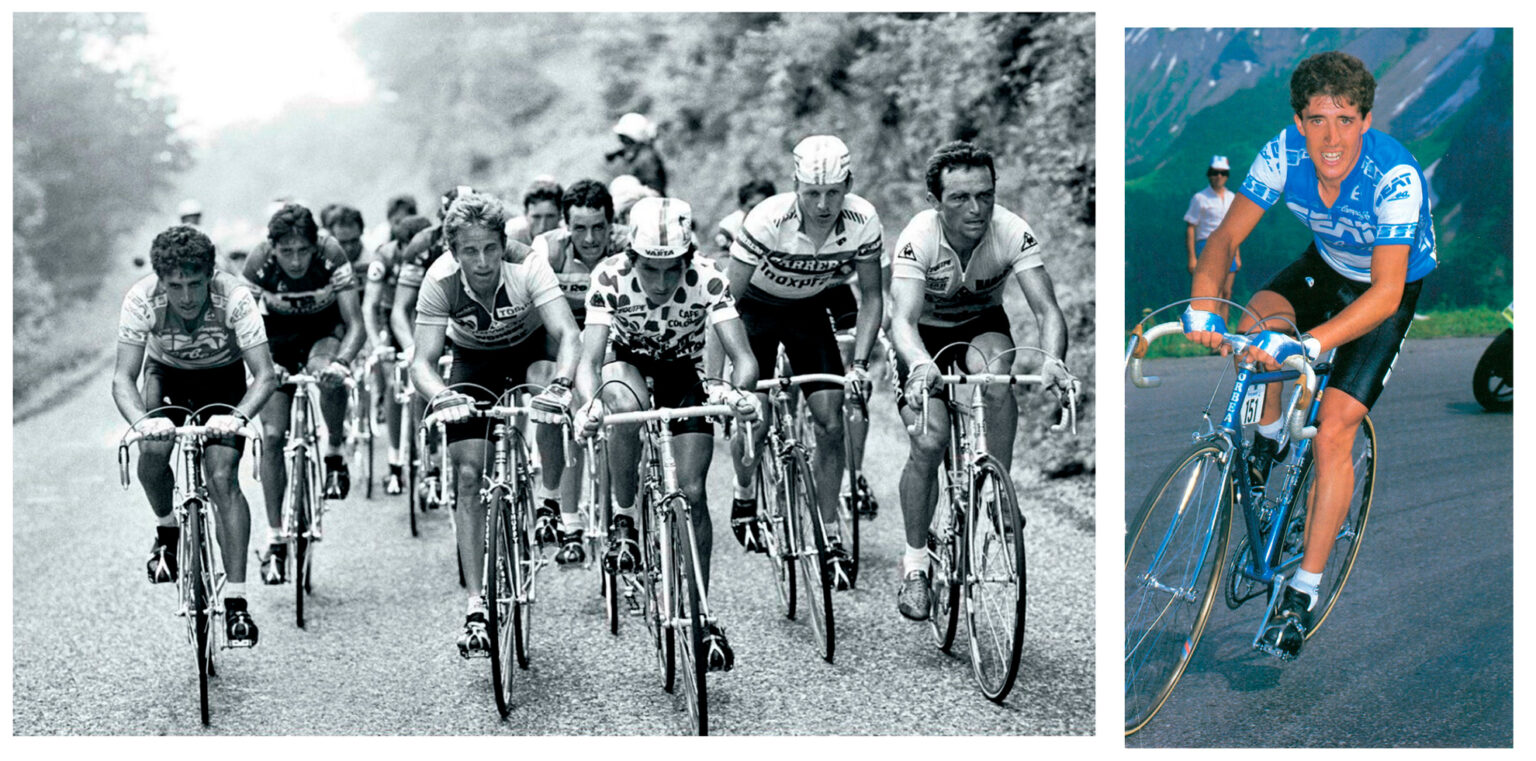

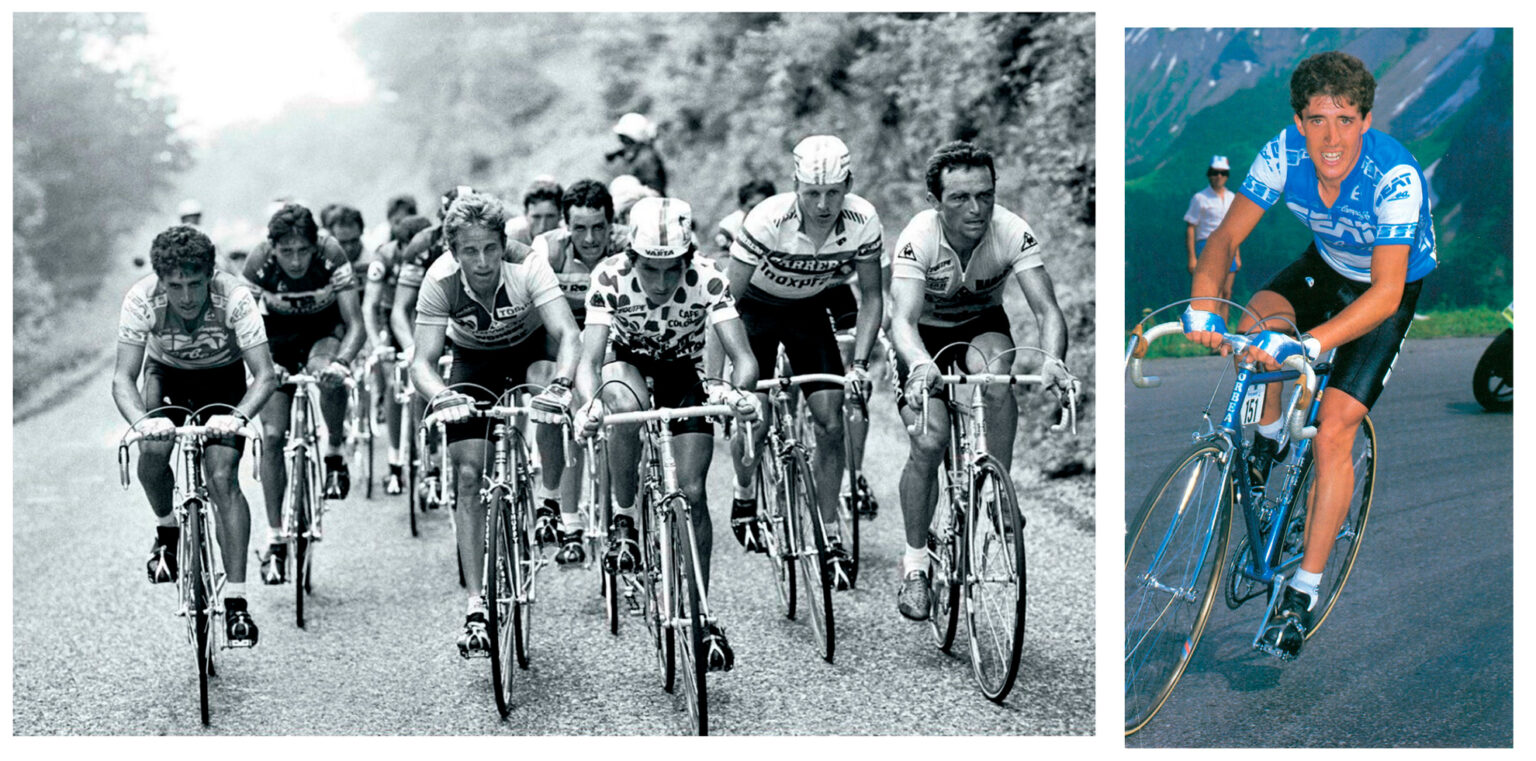

In that Tour, they experienced some epic moments, including a stage in the Pyrenees often cited as an example of a perfect team strategy. Three classic climbs – Aspin, Tourmalet and Luz Ardiden – and three Seat-Orbea cyclists launching staggered attacks – Del Ramo, Cabestany and Delgado – with Perico winning the stage. Was it really planned that way or was it an improvisation that went well?

-“Of course, we had prepared a strategy,” says Perurena.“Because we arrived in the Pyrenees with all the Basque fans waiting.“The plan was for Jokin Mujika to attack first but he didn’t have the legs that day.“In his place went Pepe del Ramo, ‘el Gato’, a little before the Aspin. He did the job for him, huh? He got a minute…”

-“Not a minute, 53 seconds,” interrupts Paco Rodrigo, who that day was in the second team car, co-driver of Pascua Piqueras, Delgado’s trainer.

“But the judges let us overtake the peloton and reach Del Ramo, so there had to be a minute difference.“Radio Tour was saying: ‘Del Ramo, 50 seconds’, ‘Del Ramo, 53 seconds’, and it didn’t go any higher.“Then I hear Txomin on the radio: ‘Atilano, go ahead, go with ‘El Gato’.”

Txomin usually calls Paco ‘Atilano’, the name of his grandfather.

-“We tried to get ahead going up the Aspin, which was even narrower than it is now, a little road full of stones, next to the ravines,” says Paco, or Atilano.

“Pascua was honking his horn to overtake the bunch.

“We managed to get to the front and we found all the favourites in the front row, blocking the road from side to side; Hinault, Lemond, Herrera, Parra, Perico… “We tried to pass them and nothing, just braking.

“We tried again and I thought: ‘You’ll see, we’ll throw these down the ravine and kill them.’ “I stuck my head out the window and yelled, ‘Zoetemelk, get out of the way’.“The guy looked at me with a face, but in the end we passed and Del Ramo crested the Aspin with a small advantage.

-“On the descent, Radio Tour said: ‘Ruiz Cabestany attacks’.

“And immediately Txomin said: ‘Tell the ‘Gato’ to breathe a little and wait for Peio’.

“Del Ramo pulled Peio between the Aspin and the Tourmalet but his strength was running out.

“Txomin asked on the radio: ‘How is ‘El Gato’ doing?’ And I said, ‘Meow!’

“Peio went alone to the start of the Tourmalet and took three minutes.”

-Peio’s greatest merit was not giving up in the previous days, because he had a cold,” says Perurena. He climbed the Tourmalet wonderfully.

“In the group of favourites, Roche attacked, Delgado countered and rode away solo.Cabestany crested the Tourmalet first, with Delgado second at 1’18”. “The others were already three minutes behind.”

With one Orbea rider leading and another in pursuit, the director had to make a decision. Paco Rodrigo remembers those tense moments in the car.

– “Pascua Piqueras belonged to Perico and I belonged to Peio, like being from Madrid and Barça,” he laughs.“Then Txomin spoke to us on the radio: ‘Tell Peio to stop. Wait for Perico. Atilano, tell him, you are friends’.”

Cabestany burst into tears when he was ordered to wait and would later say that he had seen himself as having the chance to win the stage.

-“I was suffering in the car,” admits Perurena. “Perico took advantage of the Tourmalet descent to eat, he did well, but it took him a while to get to Peio. “It seemed endless to me, but it didn’t make sense to have a rider ahead and another chasing him.“I had to stop someone and I ordered Peio to stop, because Perico had already won the Vuelta, he was strong… but it was a very tough decision.”

Cabestany emptied himself pulling Delgado and on the first ramps of Luz Ardiden ‘Perico’ moved clear.

“He gave it all, blew up and was left leaning against a wall,” recalls Perurena.

Lucho Herrera attacked from behind and flew up the mountain, cutting Delgado’s advantage, but that day a thick fog enveloped Luz Ardiden and with no television images there was no way of knowing the time differences.

“Luz Ardiden seemed very long to me,” Perurena continues.

“They said that Herrera was coming, that Herrera was coming, I was biting my nails.”

In the end, Delgado won by 25 seconds and Orbea’s tactics were vindicated.

“If Herrera had caught Perico, they’d have kicked me out,” says Perurena.

“It is normal for Peio to have a thorn in his side about that stage, because he could have won it, but we will never know.

“I made the decision and it worked out.”