The Etxeondo story: from the Villabona farmhouse to the Paris podium.

Part Two.

It comes from the first part.

By Ander Izagirre.

The move into cycling

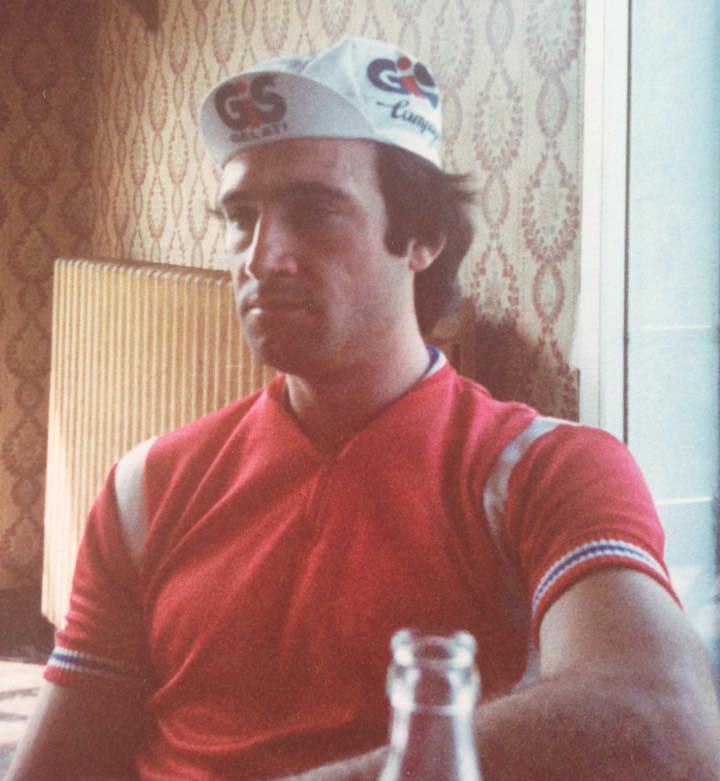

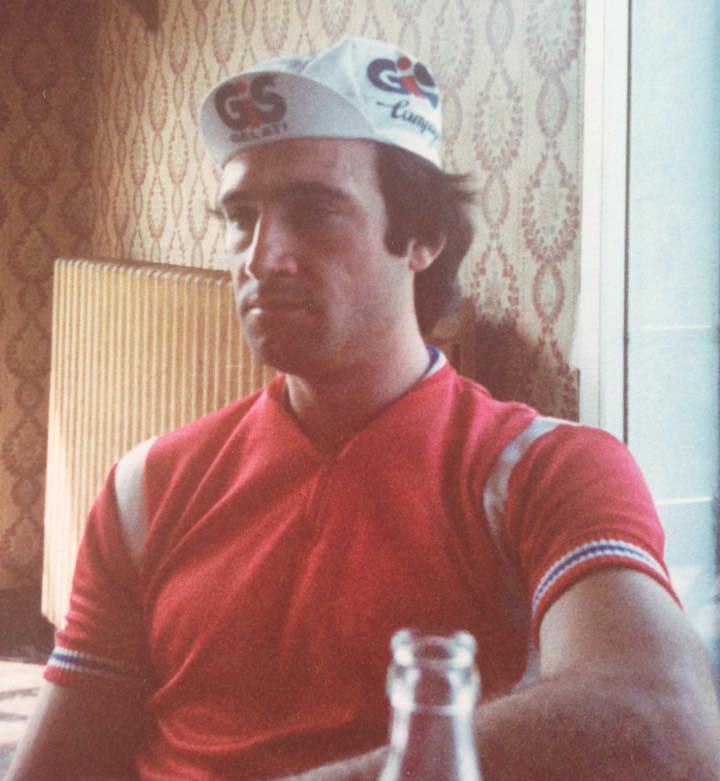

Paco became friends with Mikel, a worker at the Mondragón Orchestra record company and a cyclist at the Zikuñagako Ama de Hernani club.

Eventually, he bought a bike to ride with them and see the countryside. He noted the cyclist’s wardrobe; their needs, their customs, their fabrics and colours.

Those thick knitted wool jerseys that were too hot in summer and became loaded with water when it rained. Back then, cycling clothing was rudimentary.

“In cycling, we saw an opportunity to innovate,” explains Paco.

“But we did not choose it just for that. We grew out of the culture of the Basque Country. And here cycling is something special, it has a great tradition. We were interested in sports, health, ecology.

“There was a lot of talk about ecology in the early 80s; we also made antinuclear t-shirts,” he smiles.

“We always thought the bike was a part of that movement of freedom. We felt comfortable with that.”

What does the bike have to do with freedom?

“Everything,” he says. ”You move by your own means, in a clean way, and you go wherever you want.

“For me it is a wonderful feeling. You ride through the mountains, you pass through villages, you see everything but at the same time you are in your own bubble.

“You are free, in solitude, integrated into the landscape, perceiving everything differently.

“You can be calm, focused, in the moment.”

“Paco always says you know people by their behaviour on the bike,” adds María Jesús.

The first step into cycling was to buy a knitting machine, to make the shorts and wool jerseys of the time.

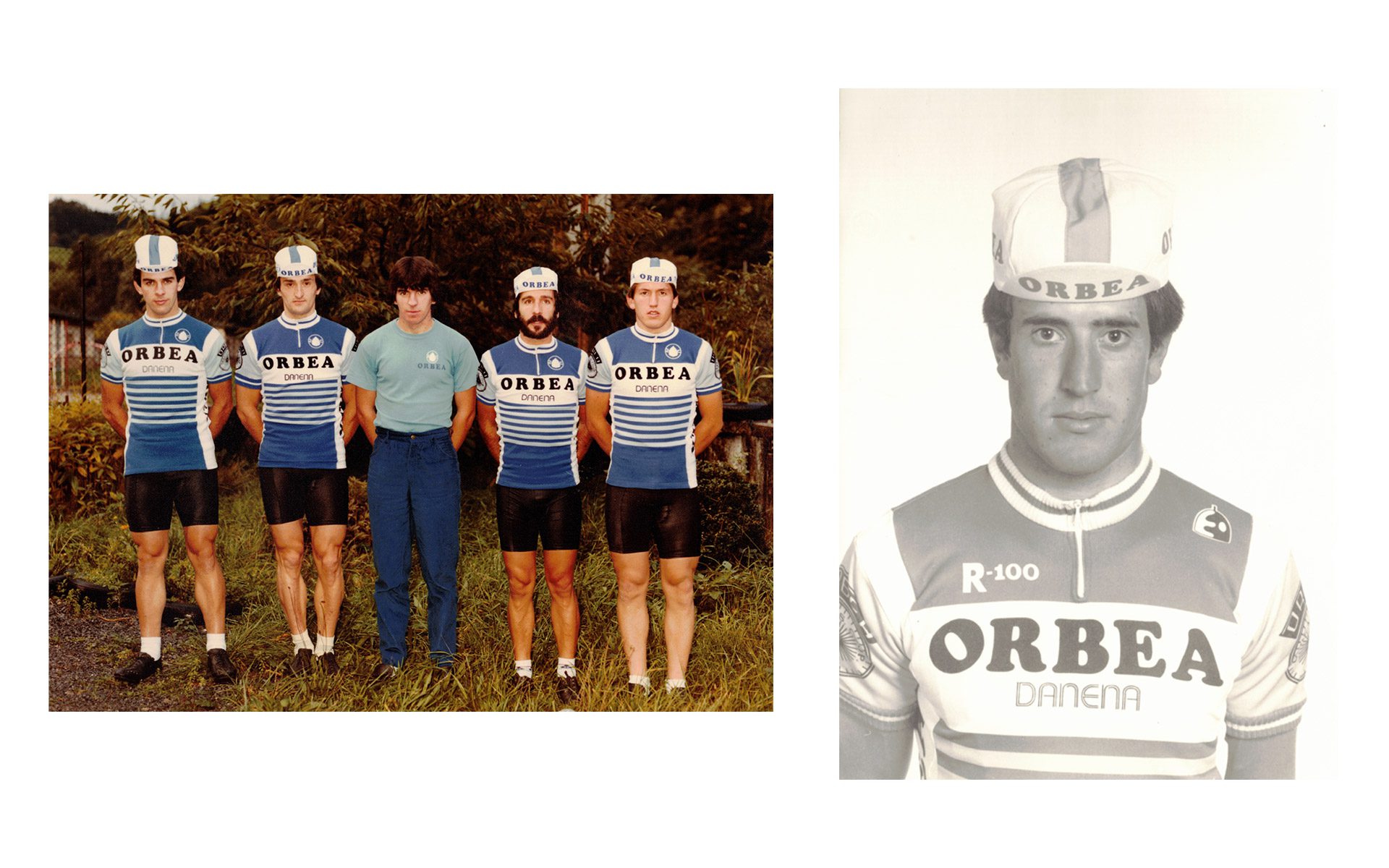

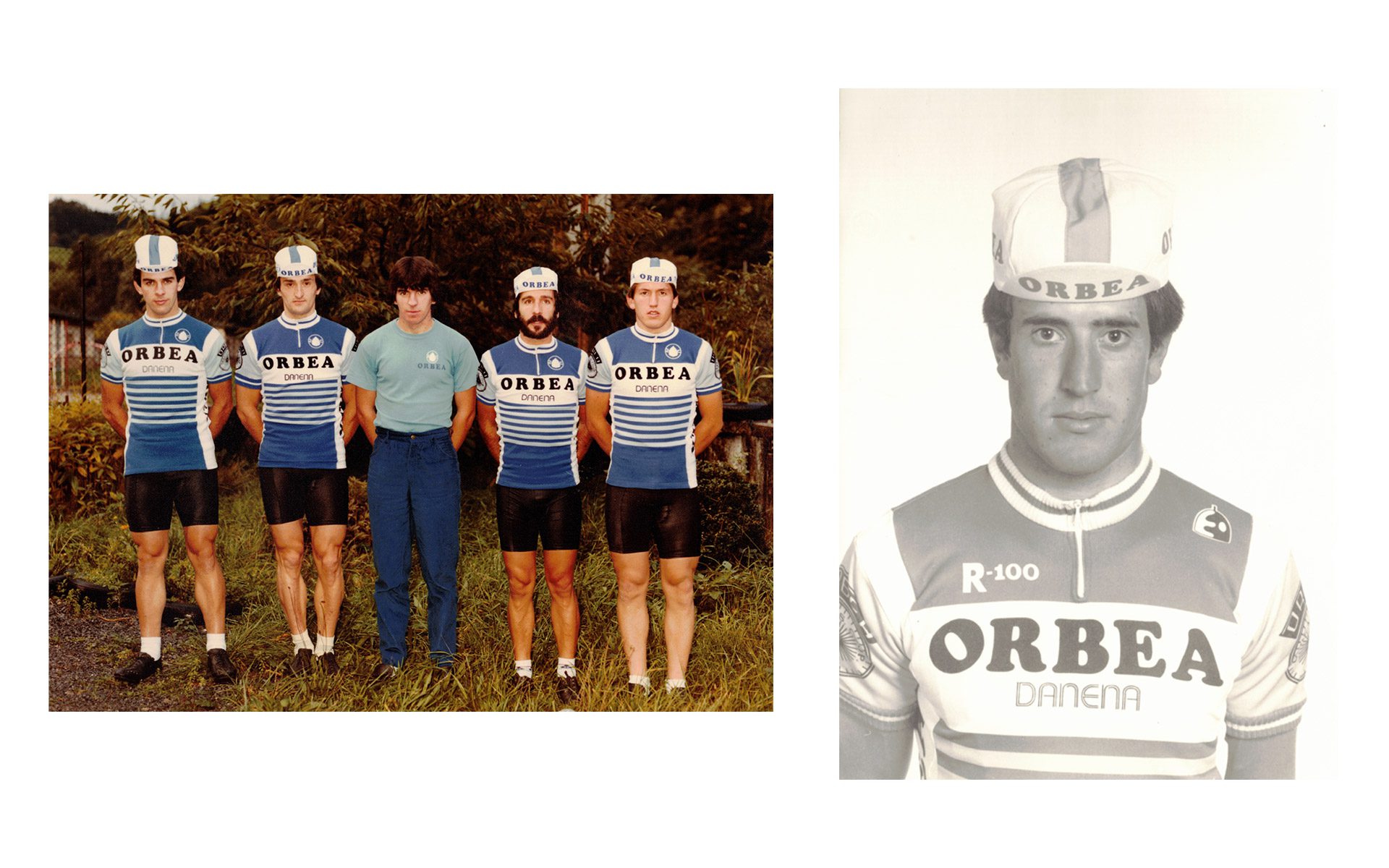

In 1979, they began to equip the cyclists of the Danena club, an amateur team from neighboring Zizurkil, and immediately made improvements.

“The jerseys of the time were bad; heavy, easily soaked,” says Paco. “We knew the new materials: elastomers, polyamides and polyesters, together with printing techniques not yet used in cycling.”

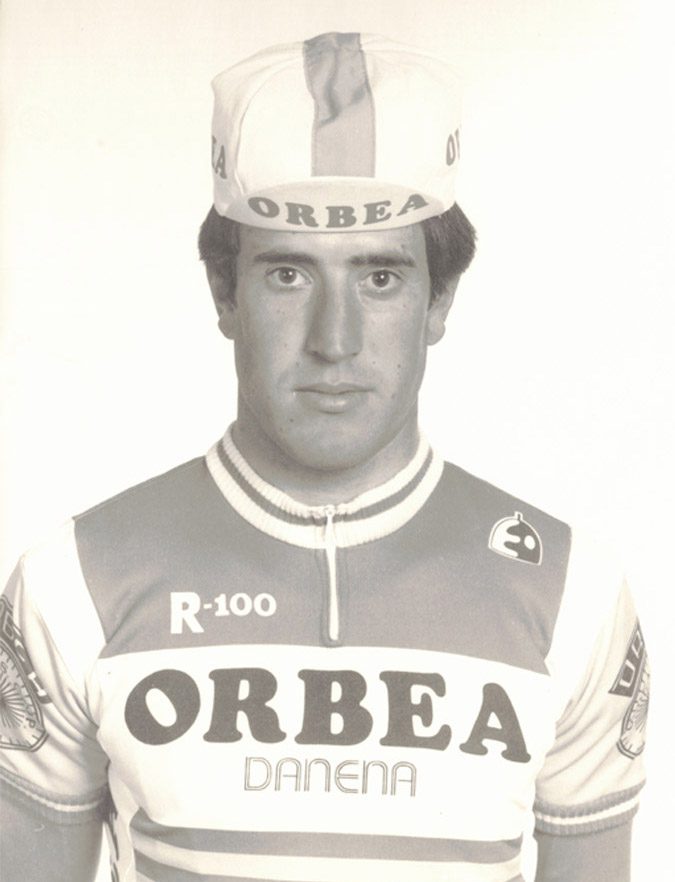

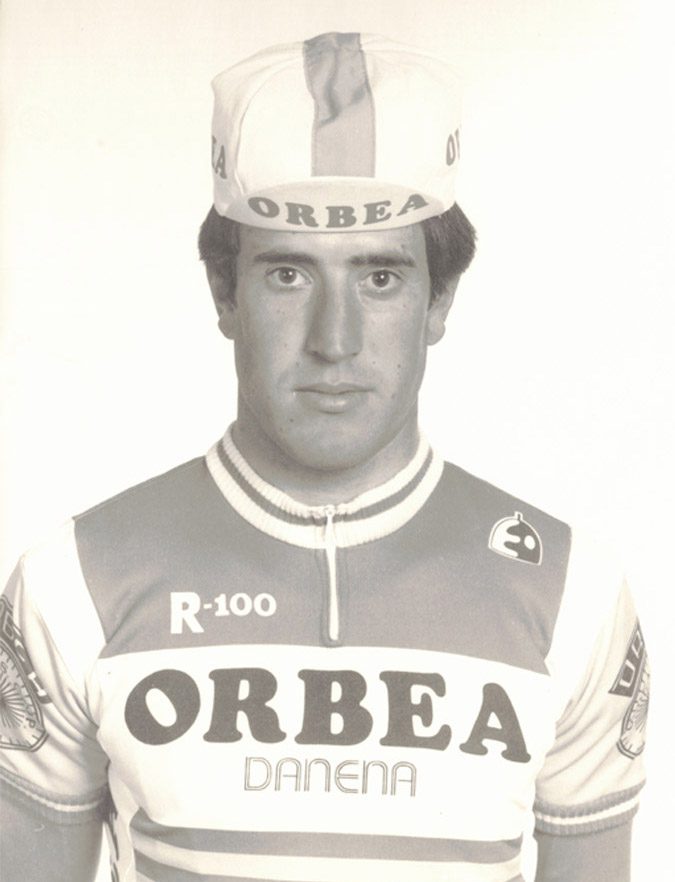

With Orbea-Danena, an amateur team that would later morph into a professional line up, they tried lightweight, elastic and aerodynamic jerseys and shorts.

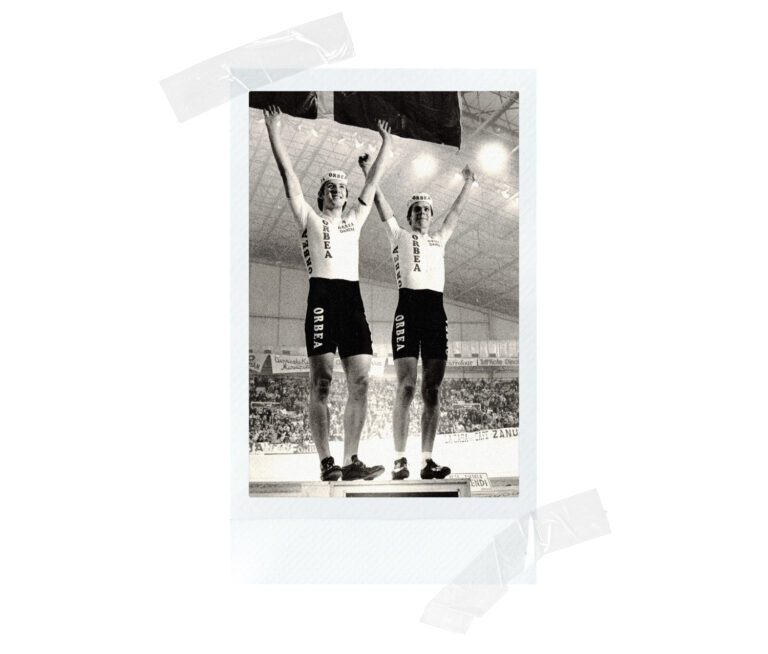

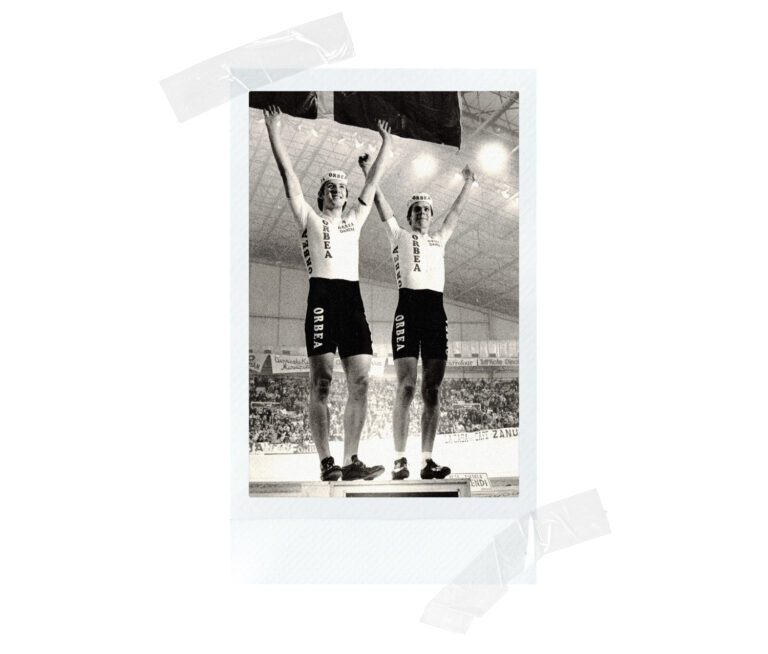

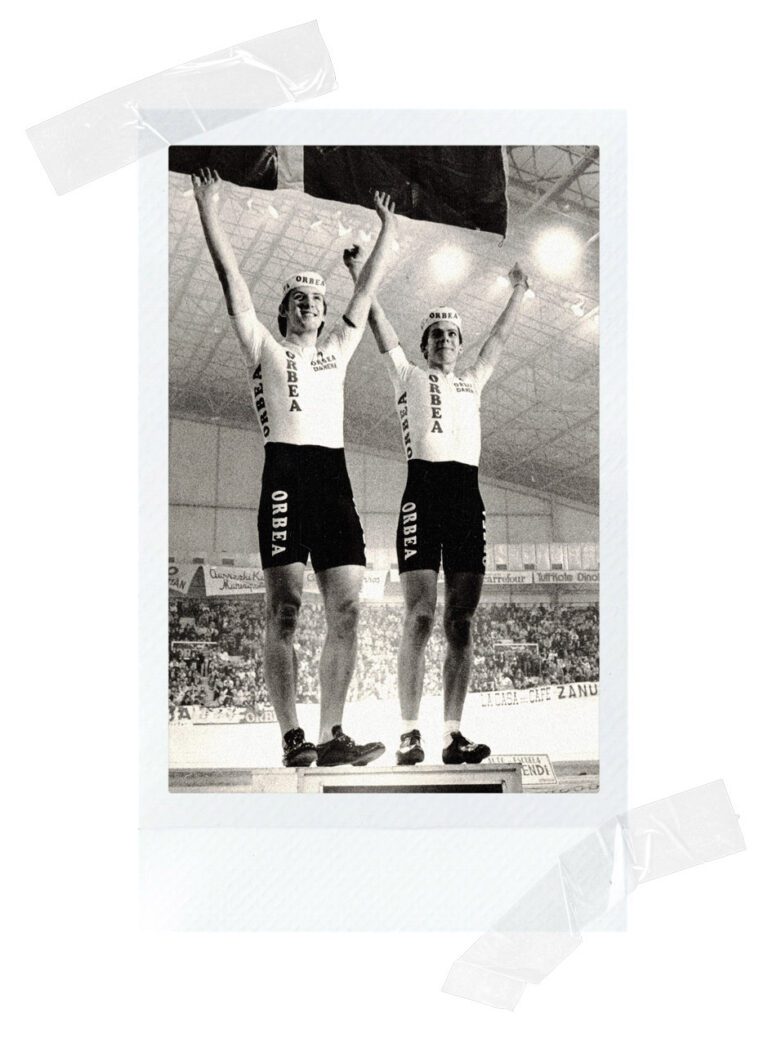

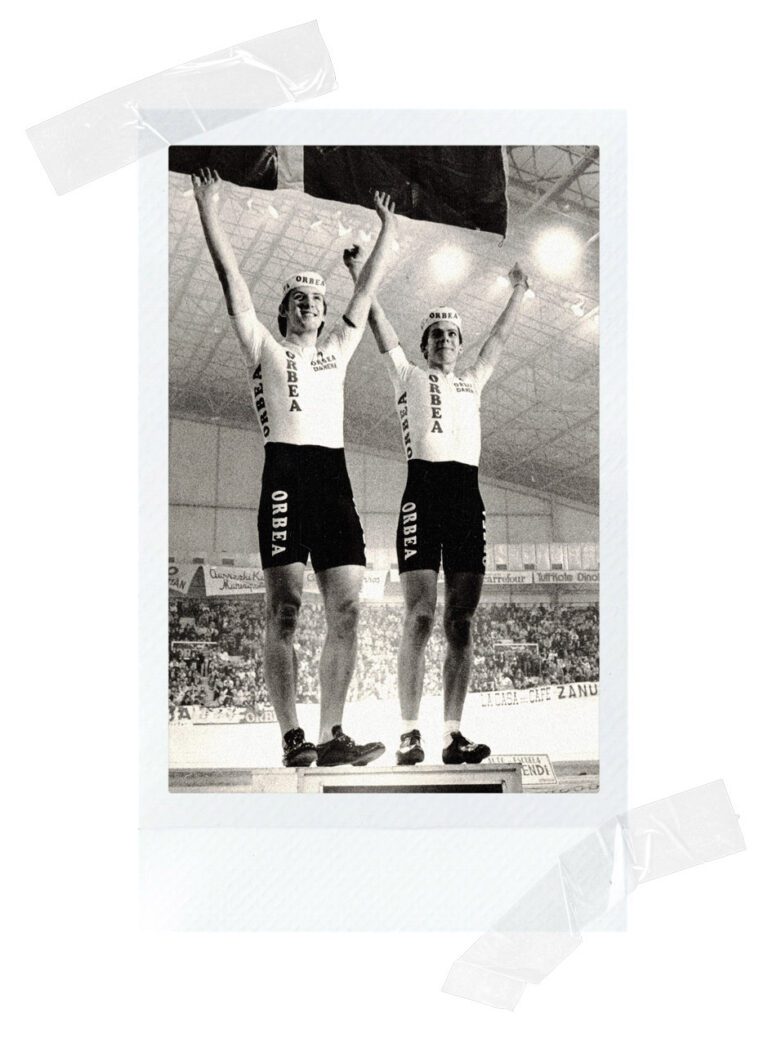

“We made Cabestany and Lekuona some skinsuits to use on the track and they won the Six Days of Euskadi, in front of professional pairings from various countries; that was a joy,” says Paco.

“We were one of the few with that level of clothing,” says Peio Ruiz Cabestany, later a winner of stages in the Tour and Vuelta and the overall in the Vuelta al País Vasco, but in the early 1980s a rider for Orbea-Danena.

“Back then we were still amateurs, but Etxeondo made us clothing the professionals still didn’t have.

“Paco was always researching materials, creating garments, doing trial and error…sometimes there was an error, eh?

“But Paco convinced you: he put a hat on you because it improved aerodynamics, because it had given very good results in the wind tunnel, and you came out with a technical advantage and above all a psychological advantage.

“You were convinced that you had the best clothing, that you were going to go faster than the others.

“I grew up with Etxeondo and their constant innovation, I signed up for everything.

“Veterans were freaking out. We went out to the track crammed into a full black jumpsuit, which covered even the fingers of your hands, with our name in yellow on the back, a helmet with a black lycra cover.

“Paco did what he wanted and I always bought into it.”

Etxeondo was also involved in the first women’s cycling team, Orbea in 1985.

“Until then, we girls used to wear tracksuits, just imagine,” says Arantxa Orbegozo, one of the five Orbea pioneers, along with Amaia Elosegi, Josune Gorostidi, Carolina Sagarmendi and Dina Bilbao, who were all between 17 and 24 years old.

“One day, they called us to go to the Etxeondo factory to pick up new clothing.

“We were amazed to see ourselves dressed as cyclists, with the same clothes as the professionals, but we were also embarrassed to wear those tight shorts, with that thick pad.

“The jerseys were narrow in the chest and wide in the middle of the body. There was no women’s clothing, it was men’s clothing.

“And we did not know journalists would come: they took pictures of us, dressed as cyclists but me in mountain boots, someone else in sheepskin boots, the other in street shoes. Wow, when we saw each other in the newspaper.”

Ainhoa Artolazabal, from Toulouse, was in the next generation of riders. Twice champion of Spain, she rode in several World Cups and the Barcelona Olympic Games and vividly remembers her first shorts:

“We were three cycling sisters,” she says. “As girls, we used to cycle with my father from Tolosa to Hondarribia to spend the day.

“Shorts were expensive then, so we had to make do with athletic shorts. Even riding to Hondarribia with those little pants…huff.

“One day, my father took us to Villabona, to the Etxeondo farmhouse, and we bought our first shorts, the kind that were still made of wool.”

When she went to competitions, says Artolazabal, the clothing of the day meant there was one item that could never be absent from her suitcase:

“Nivea skin cream,” she says. ”The chamois were made of natural leather, hard, rough; we had to put the cream on to soften them, because the chafing and pain were an ordeal otherwise.”

“We called him Paco The Pad,” laughs Cabestany. “Because he was obsessed with chamois all day, everyday; doing tests, looking for improvements.

“He made the first synthetic pads and they already made a huge difference.”

The greatest sufferings of those pioneering female cyclists came from sitting for hours on bicycles designed for men, on saddles designed for men, with clothes designed for men.

“You don’t know how many problems with boils and fistulas we had,” says Orbegozo, who continues to ride four decades later and marvels at the evolution of saddles and shorts designed for women.

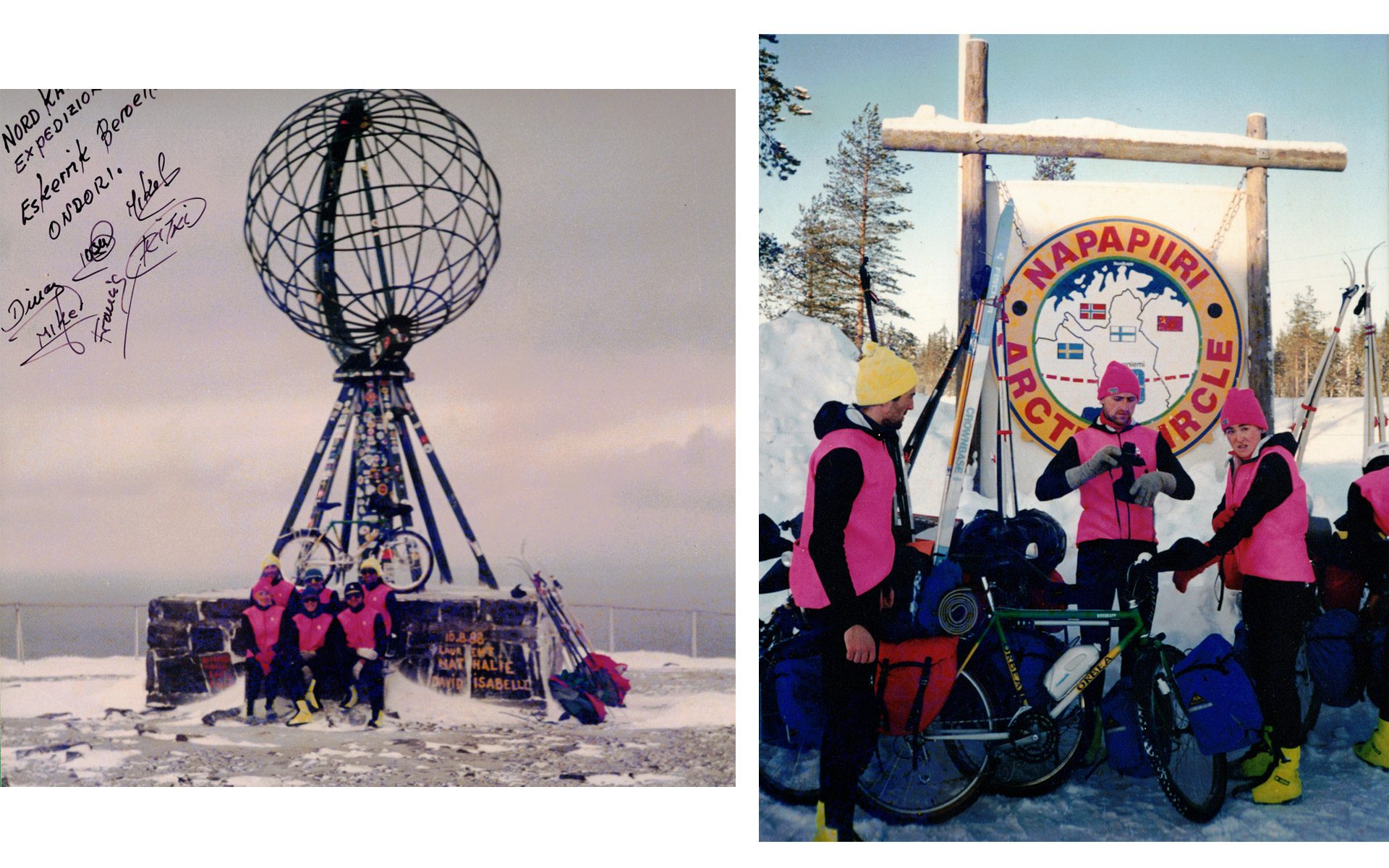

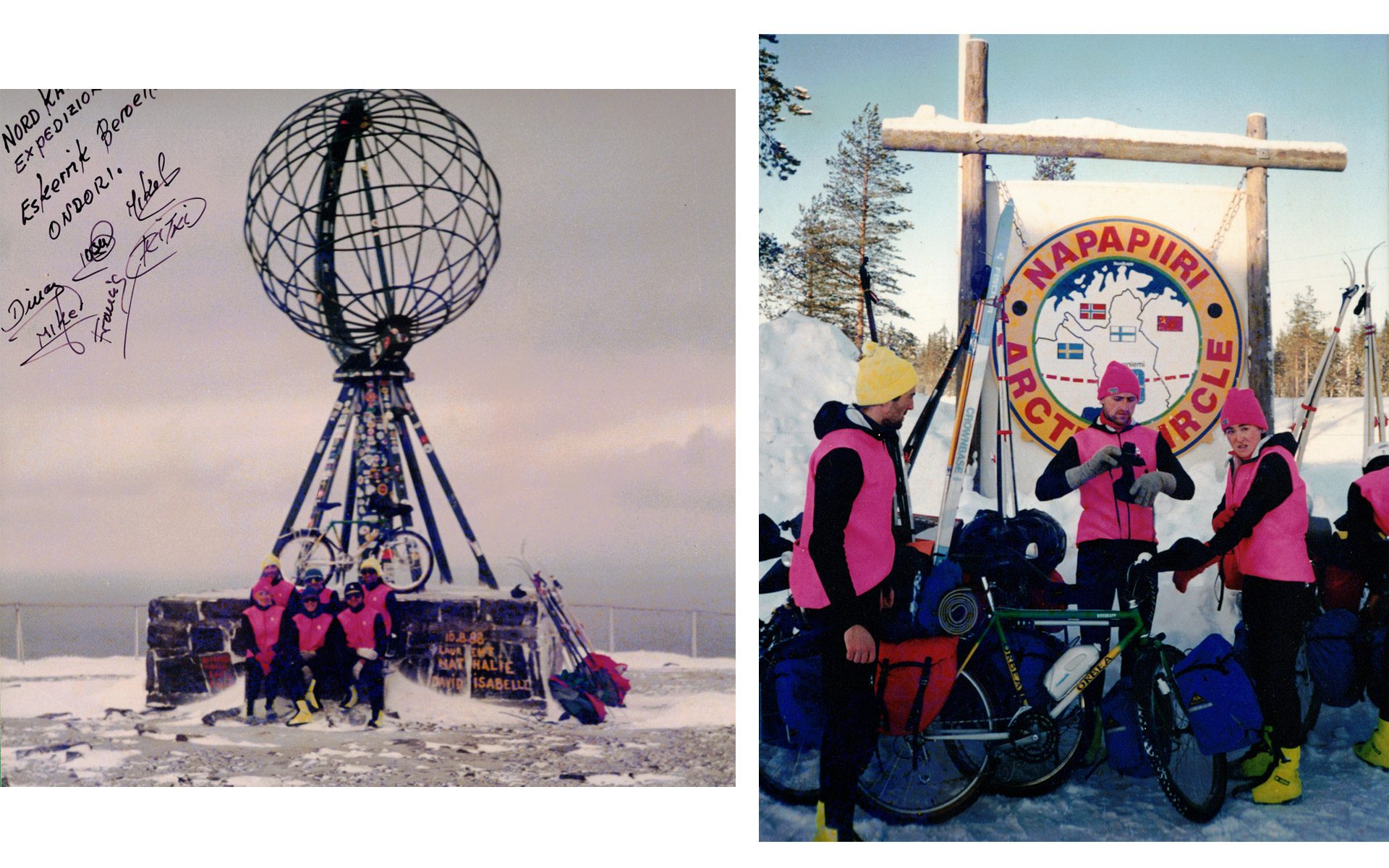

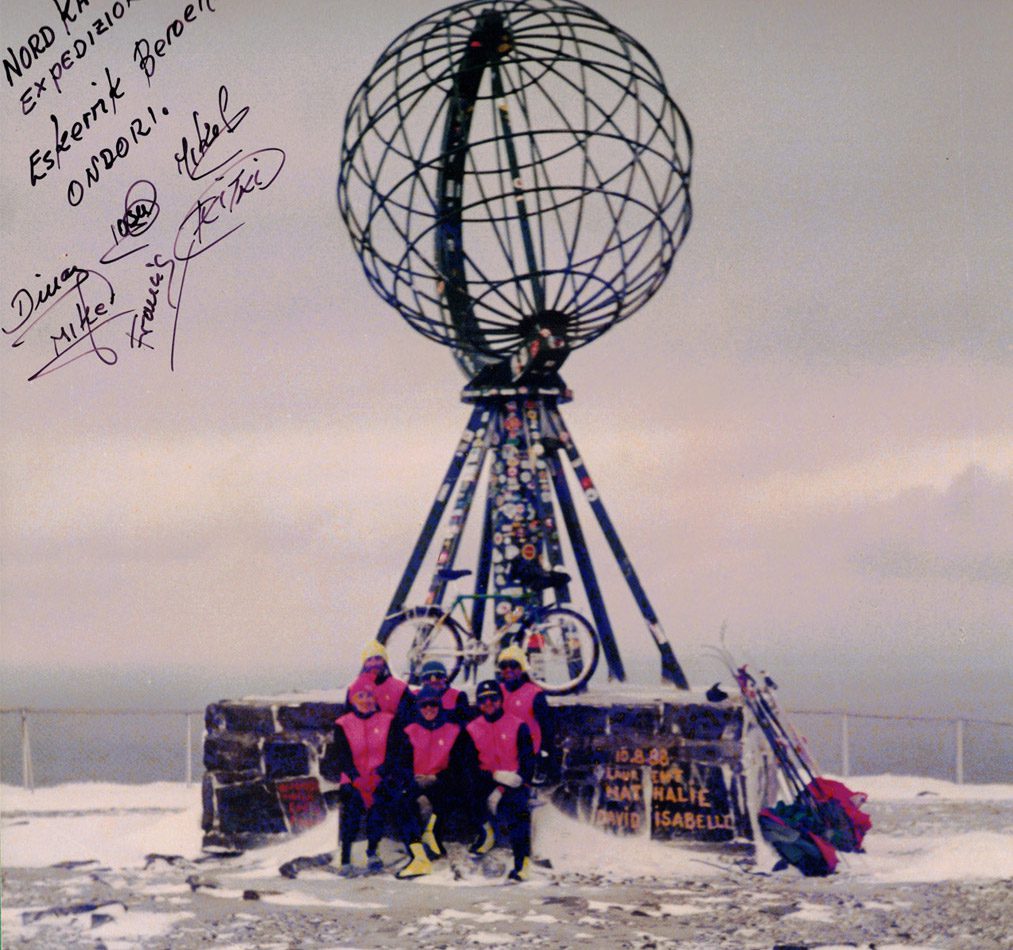

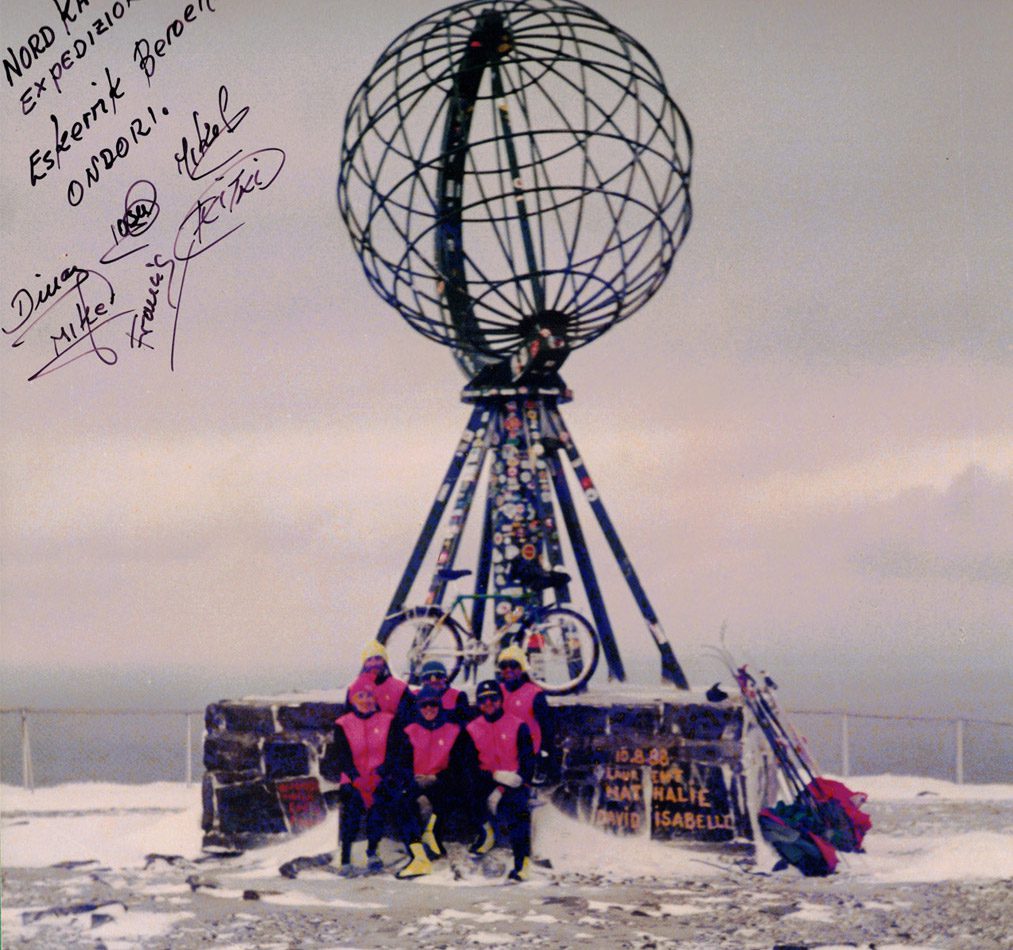

“The clothes have improved a lot, but Paco always gave us a hand, in the days of the Orbea team and also later, when he gave us clothes for bike expeditions in the middle of winter.

“Before, when it was cold, we wore five layers of shirts and jerseys , two short shorts above the long shorts, we were like onions. Now you put on a long thermal shirt under your jersey and you are no longer cold, it’s amazing.”

Those women, pioneers of the Orbea team, have received tributes in recent years: at the Clásica de San Sebastián, during the Pedro Delgado cycle tour in Segovia and in the Marino Lejarreta ride in Ordizia.

“I was very surprised, ” says Orbegozo. ”We spent all our youth hearing ’But aren’t you going to work? But aren’t you going to have children?’, feeling everyone looked at us like we were crazy.

“Suddenly, thirty years later, they present us everywhere as references. I was moved that Leire Olaberria (Olympic and World Championship medalist) said that without our example she would not have been a cyclist.”

To the tour podium

As he travelled along this path toward better and better garments, in 1982 Paco bought “the best camera” and travelled a few days with Javier Mínguez’s Zor team to the Giro d’Italia, to spy on how the Italian, French, Dutch and Swiss teams dressed.

His conclusion? “We were not far from the rest of Europe.”

But when Etxeondo began to move into the market, some buyers and distributors were sceptical.

“In those years, when the political environment in Spain was so harsh, any Basque name sounded suspicious,” recalls Paco.

“What a name: Etxeondo! And the logo with the goal looked like a redneck thing to them.

“‘Why do you put this mokordo (shit) here?’, someone once asked me.

“But I always thought ‘And why not?’. That has always been my phrase. There are things that seem inappropriate to many but make a lot of sense to us.

“From a marketing point of view, it would have been better to have an English name and a bird as a logo.

“But Etxeondo was us, it was the village where we had worked and created so many things, it was our love. We believed in it.”

“There was no marketing plan or anything like that, it was our life. And life like that was much more beautiful,” María Jesús smiles.

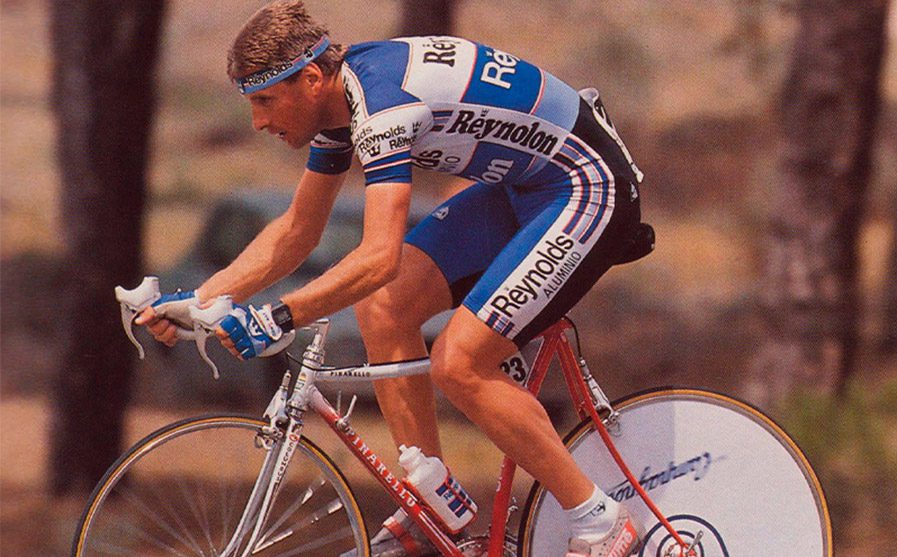

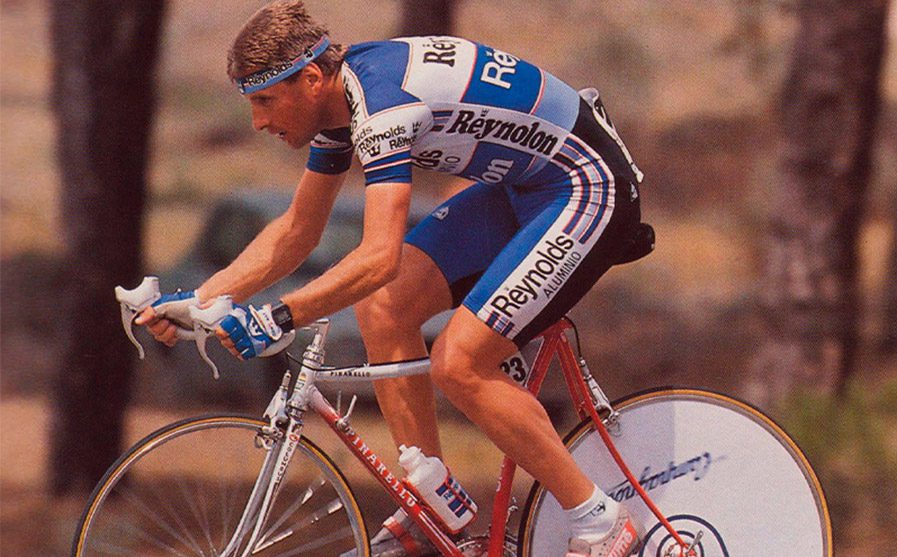

The great international breakthrough came in 1983, when Etxeondo equipped two professional teams: Zor and Reynolds.

“Spanish cycling was in a desert, since the years of Kas and Fagor, no one had really emerged,” said Paco.

“It was a grey time, with little ambition, an inferiority complex, the teams hardly left Spain. They were also very stagnant with their clothing.”

In the 1983 season, the revolution broke out. The Vuelta a España was broadcast live on television for the first time with extraordinary success. More sponsors arrived and budgets, salaries and investment in materials increased.

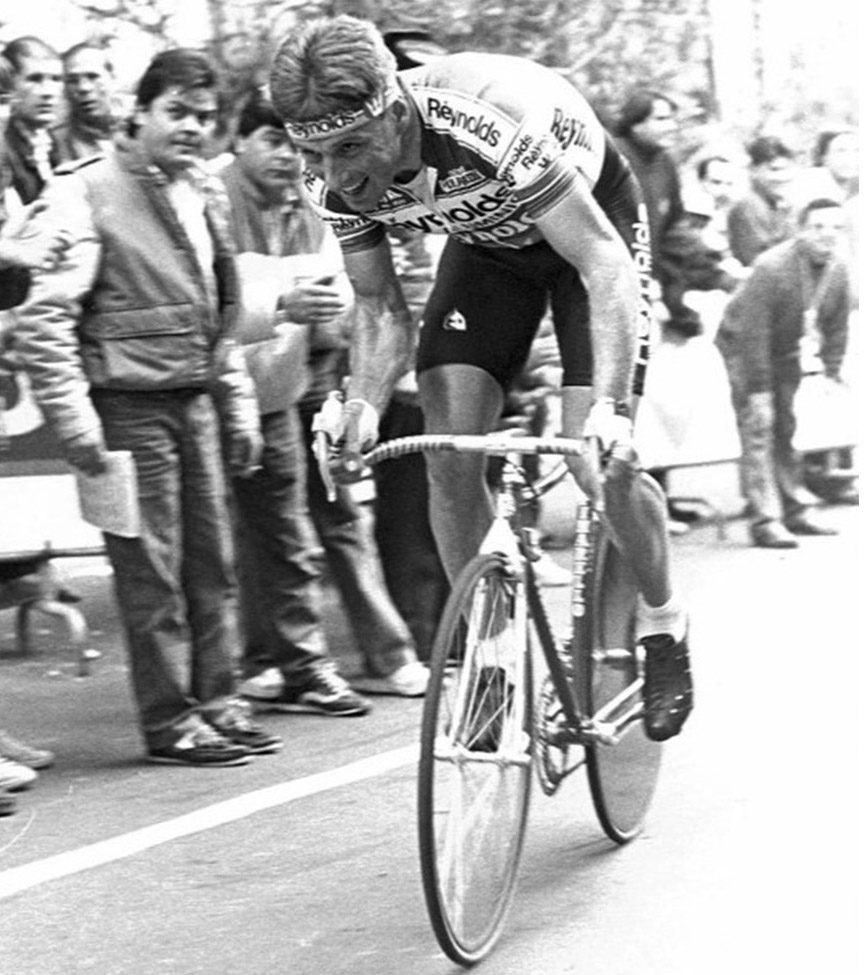

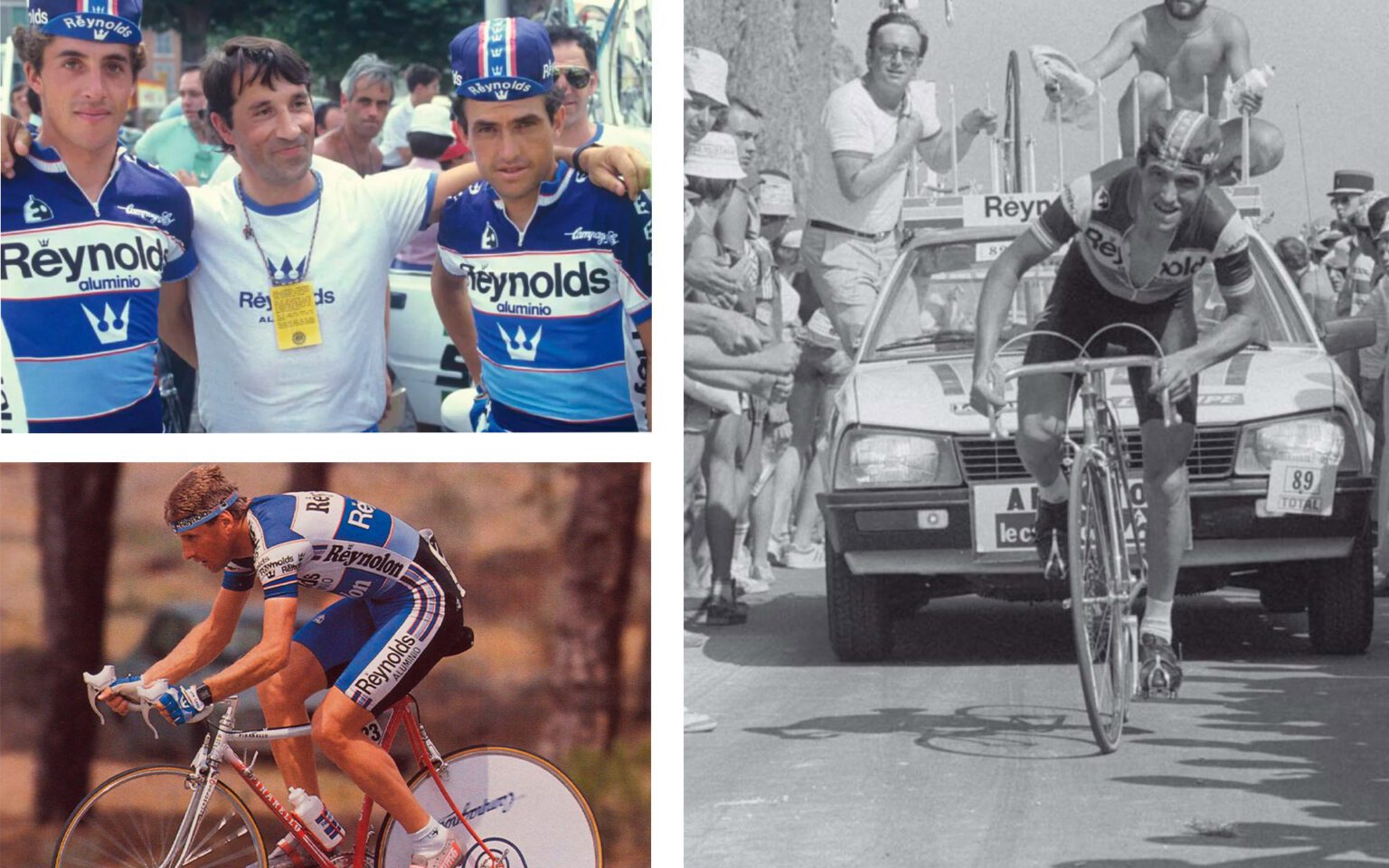

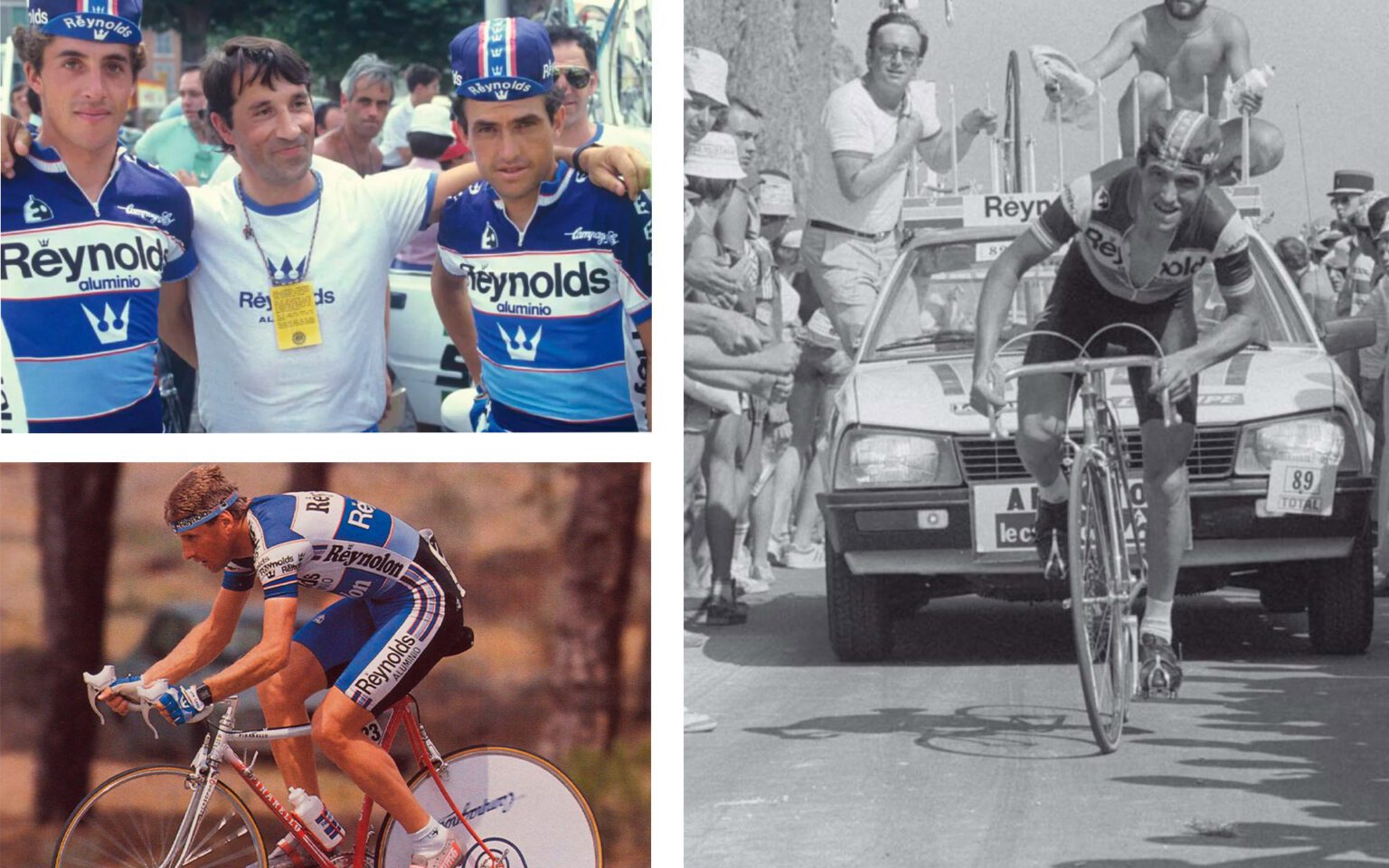

And above all, the mentality changed. Reynolds was a young team led by José Miguel Echávarri from Navarra, Paco’s friend, and captained by Ángel Arroyo, Pedro Delgado, Julián Gorospe and José Luis Laguía, who went to the Tour to compete without fear.

“They had ambition and open minds,” says Paco.

“We changed their clothes: we went from wool to lycra. We created the fabrics, we did a thousand tests, we convinced the directors and the cyclists.

“It was not easy. Some of the older riders resisted initially; it was difficult for them to change from their usual material.

“With the wool they felt more protected, the lycra gave them a strange feeling. It was very tight, very light, they felt almost naked, they thought they were going to be cold.”

Paco remembers the day they tried on some light shorts, with a thin pad, that did not quite convince some.

Amid the complaints and doubts, Arroyo approached him: “Paco, don’t pay any fucking attention to them, these shorts are extraordinary. You go ahead.”

Arroyo never backed down, says Paco. He was a harsh Castilian, with clear ideas and no fear of anyone.

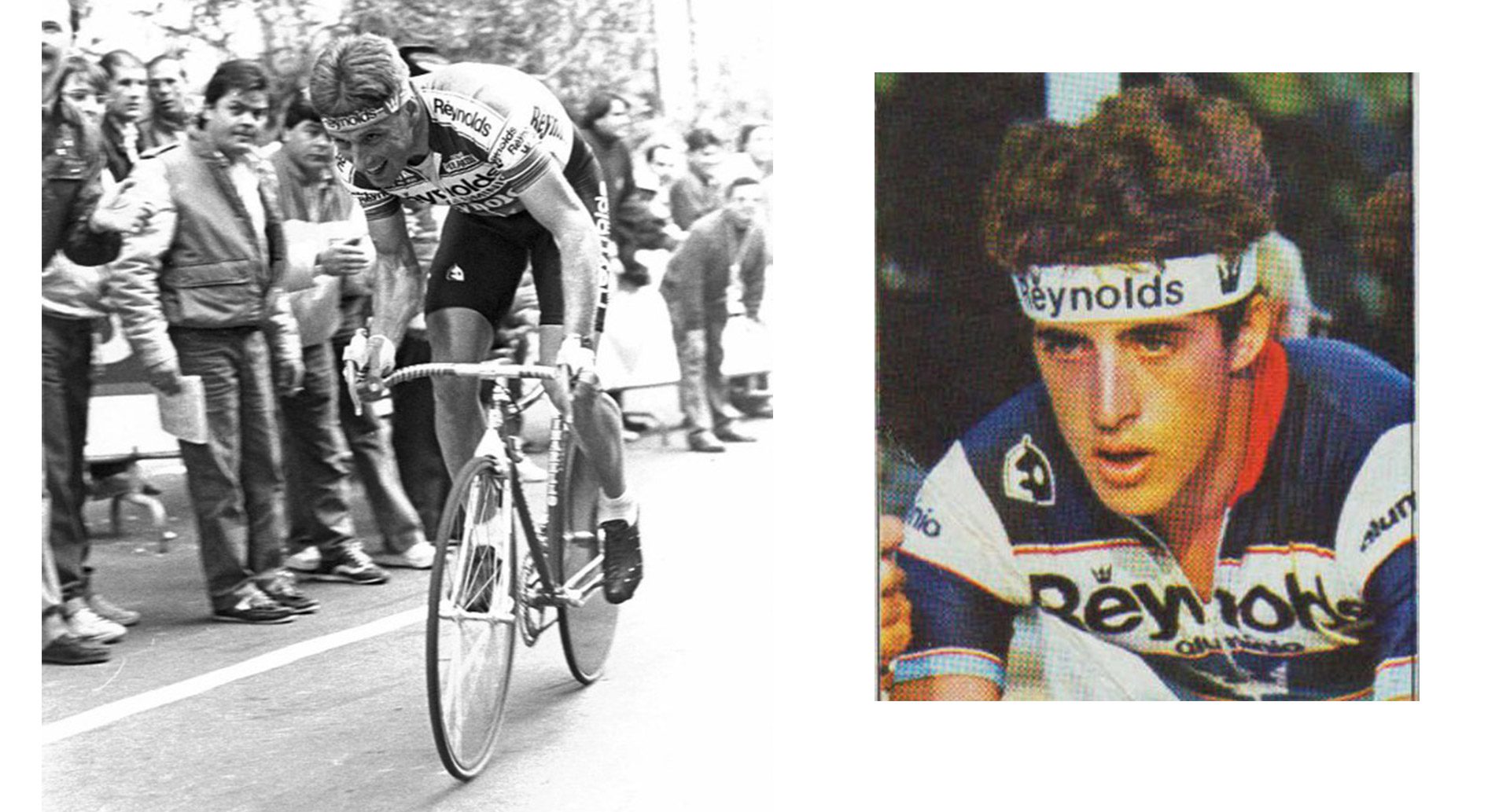

The young riders were the most daring on the road and the most willing to try out the new items in their wardrobe, even those the older riders found ridiculous, like the sweat-wicking headband, an innovation from tennis.

“Gorospe, he loved the headband,” says Paco. “It was modern, it was functional but it was also an image.

“Gorospe put it on, Delgado put it on, they were on TV like that…and all the cyclists bought it.

“We put a sheet on the headband we could print on, to personalise them, to put our logo and that of the team on.”

Or the aerodynamic hat for time trials and quickly adopted by Peio Ruiz Cabestany and Miguel Induráin, among others.

“I lived for cycling,” says Cabestany. “Every day I concentrated on training well, eating well and sleeping well.

“I realized that Paco was the same in his field; he lived for Etxeondo, to find the best materials and make better clothing.

“He behaved like an elite athlete, but focused on clothes.

“He was obsessed with perfection. He didn’t like a jersey to crease, to wrinkle.

“He also cared about keeping to his own path. One of the world’s largest sportswear brands made him a dizzying offer to make the clothes for them, but he wanted to get on with his own business.

“Offers like that might have set him up for life, but he bet on his own future.

“I remember him saying to me: ’If later things go bad for me and I have to earn a living collecting snails, I will collect snails. But I want to keep my project’.”

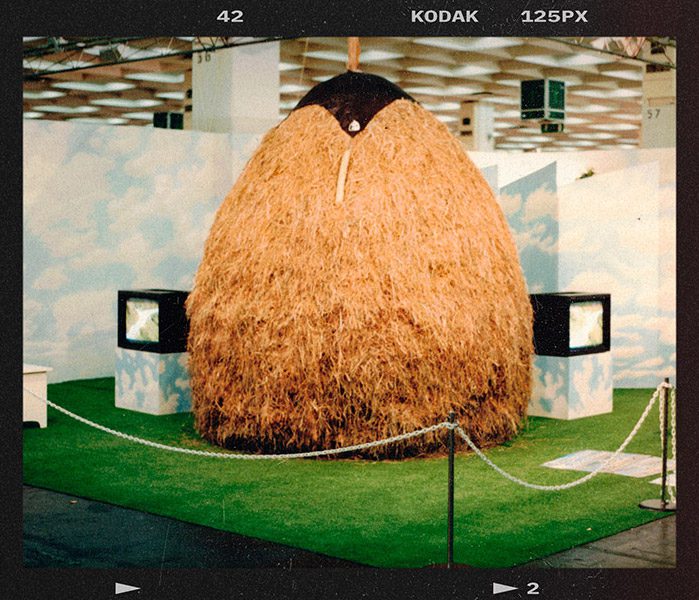

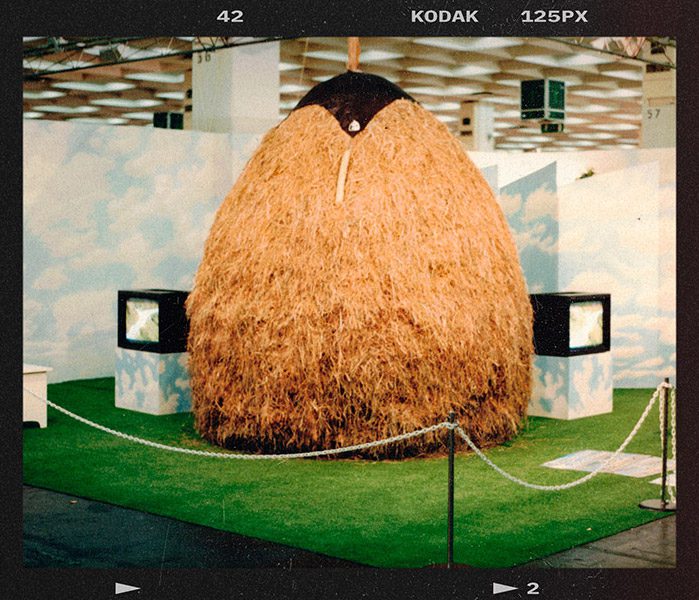

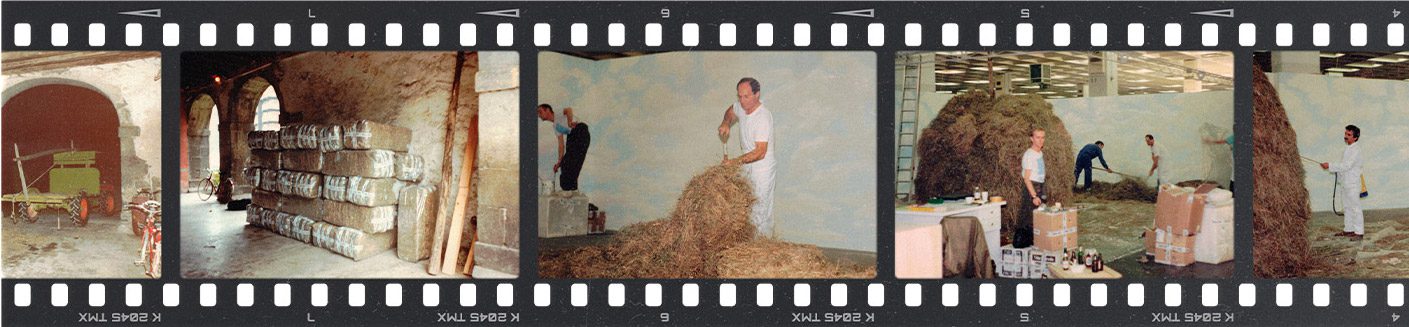

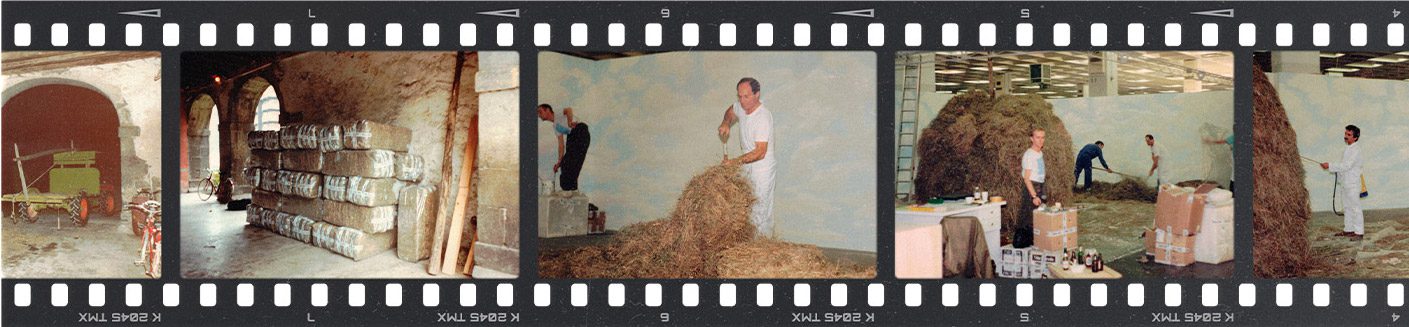

Cabestany laughs when he recalls Etxeondo seting up a big pile of straw on their stand at the Frankfurt cycle show. The brand was expanding across the world, but taking the spirit of the farmhouse with them from one country to another.

Etxeondo’s debut on the Tour came in 1983, when Reynolds blitzed the race: Arroyo won the time-trial at Puy de Dôme and finished second in Paris behind Laurent Fignon, while Delgado astonished the world with suicidal descending and three second places in high mountain stages.

And some of their innovations, not just in clothing but also in footwear, threw the establishment off balance.

Reynolds riders wore white shoes on some mountain stages, because they absorbed less heat than black ones, and received fine after fine because the Tour, always so conservative, stipulated shoes had to be black, serious and traditional.

Etxeondo would have other battles with the French years later, to keep the Kas team in their predominantly yellow kit that, traditionally, the organisers did not allow.

The Zor team was not far behind in the 1983 Giro either; winning the team classification, while Alberto Fernández took two stages and filled the third step on the final podium behind Guiseppe Saronni and Roberto Visentini.

“Suddenly we were there, with the best teams in the world,” says Paco.

And from there, what was the objective?

To give them the best clothing in the world, of course.