The cyclist who cycled for 50 hours straight

by Ander Izagirre

The cyclist who cycled for 50 hours straight

by Ander Izagirre

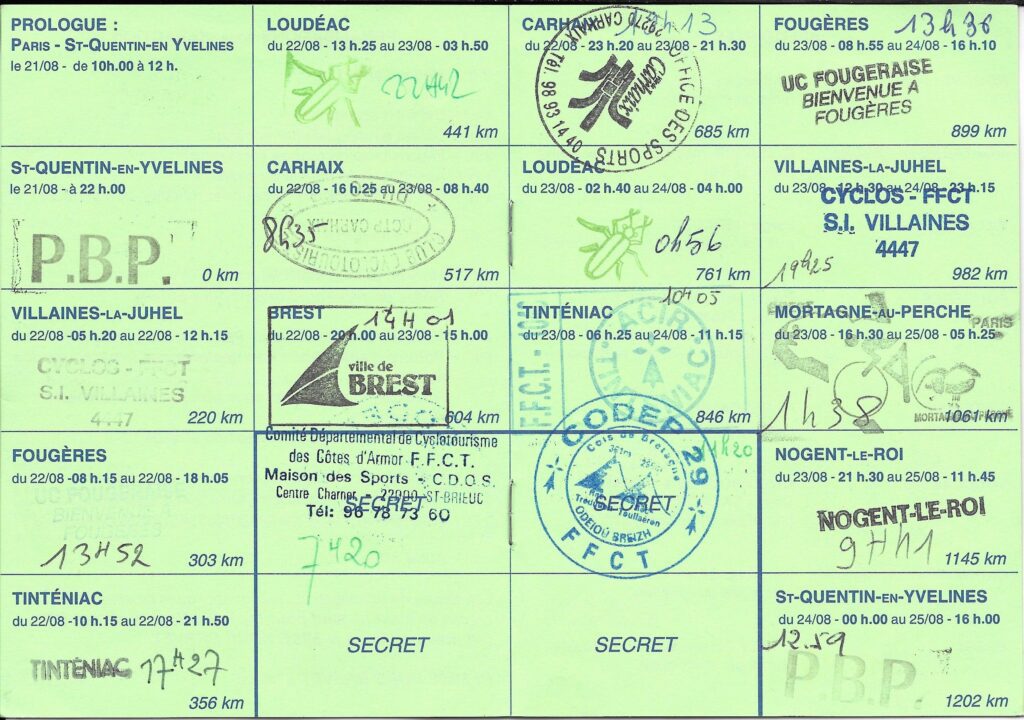

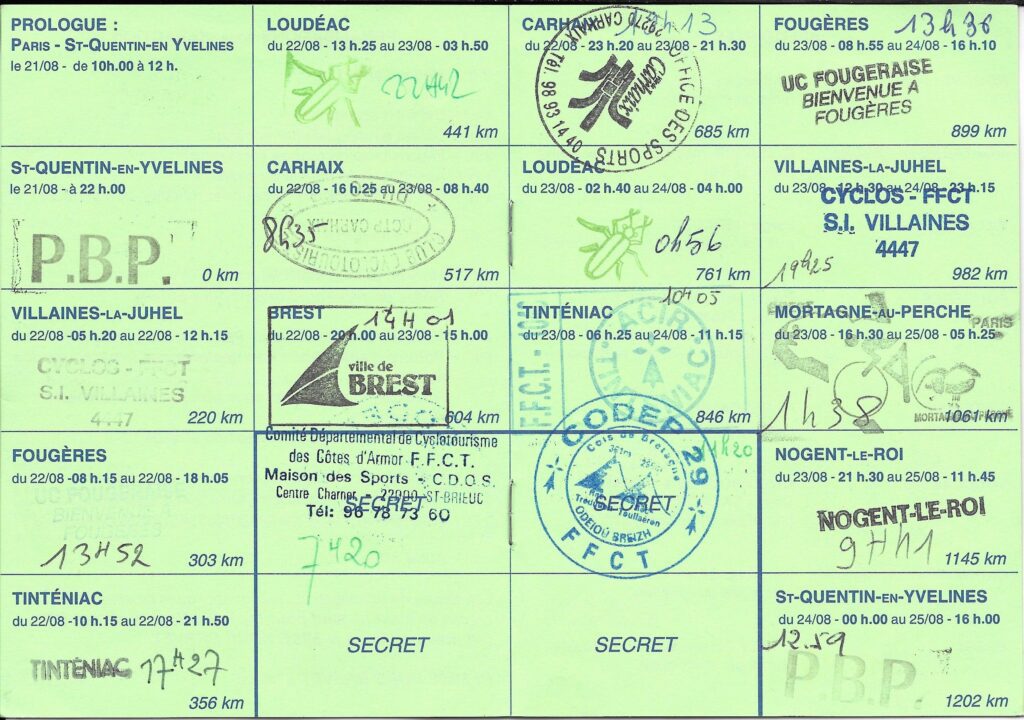

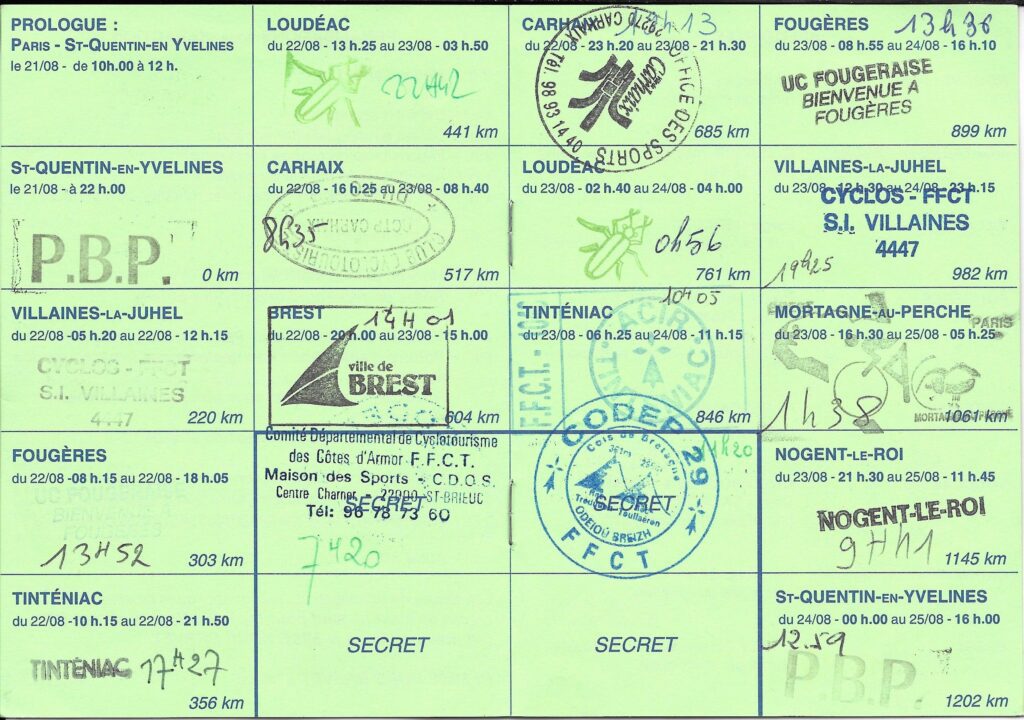

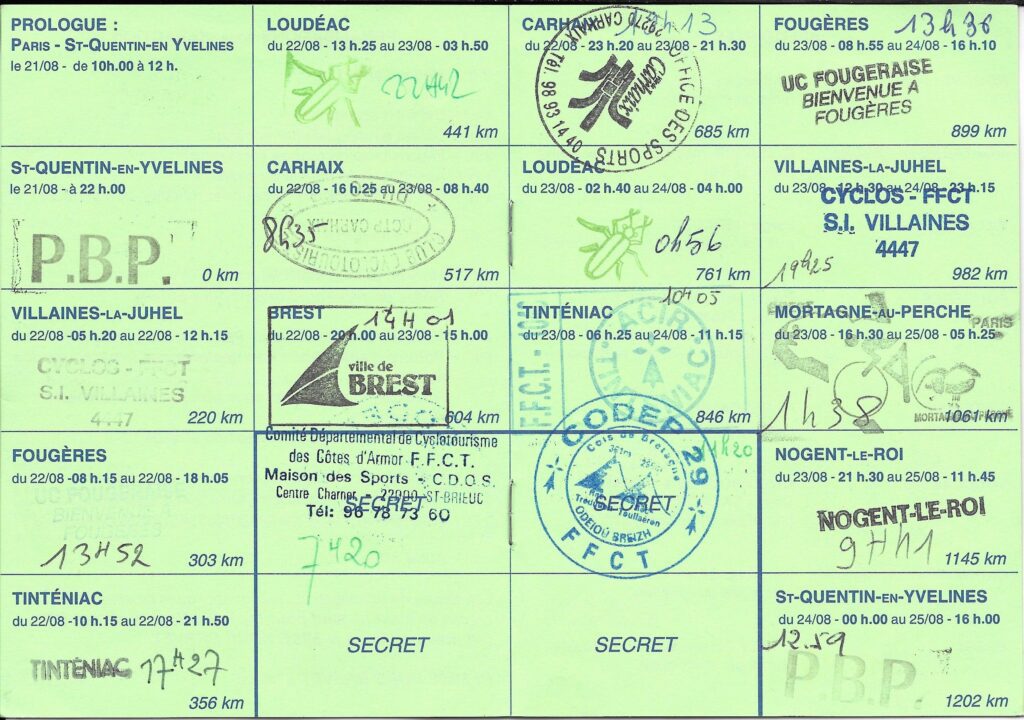

In the 1990s, a little-known cyclist wore Etxeondo’s most advanced garments even before the professionals: Alberto Guisasola, a doctor from San Sebastian who was passionate about ultra-distance races such as the 1,245-kilometre Paris-Brest-Paris. In 1995, together with eight other cyclists, he set the record for the race: 43 hours and 20 minutes. Always with the same shorts, yes.

Guisasola developed an early passion for long distances. At the age of 13 or 14, even before competing as a cadet, he would set off with his bike at dawn, cycle 160 or 180 kilometres and return home at the end of the afternoon.

Many cyclists sleep for a while on the second night, but Guisasola did not do so in any of his three participations.

– Second night without sleep: that’s when you enter another dimension. You don’t see the road well, you have visions, your perception tricks you…. There was a moment when I was crouching in the dark because it seemed to me that I had to pass under a kind of bridge that didn’t really exist. Many people fall asleep and fall into the gutter. You can’t train for that, but you have to be prepared for that moment to come. You’re exhausted, it’s cold, you get sleepy and you have to concentrate. And you also have to keep up the pace, because the speeds don’t slow down during the night. When the sun comes up it’s incredible, your body recharges with the light, you get a rush and you finish much better.

Temperature changes, rain and wind are also common obstacles. For this reason, and because of pedalling for so many hours in the same position, clothing is essential.

– In 1987, I went out with an Etxeondo bib shorts, one that I had bought myself because they were the best. The bibshorts had seven thousand kilometres on them, and I didn’t want to take any risks with a new garment that might rub against me. The chamois ended up looking like cigarette paper, it was almost falling apart, but I didn’t feel any discomfort.

Many cyclists sleep for a while on the second night, but Guisasola did not do so in any of his three participations.

– Second night without sleep: that’s when you enter another dimension. You don’t see the road well, you have visions, your perception tricks you…. There was a moment when I was crouching in the dark because it seemed to me that I had to pass under a kind of bridge that didn’t really exist. Many people fall asleep and fall into the gutter. You can’t train for that, but you have to be prepared for that moment to come. You’re exhausted, it’s cold, you get sleepy and you have to concentrate. And you also have to keep up the pace, because the speeds don’t slow down during the night. When the sun comes up it’s incredible, your body recharges with the light, you get a rush and you finish much better.

Temperature changes, rain and wind are also common obstacles. For this reason, and because of pedalling for so many hours in the same position, clothing is essential.

– In 1987, I went out with an Etxeondo bib shorts, one that I had bought myself because they were the best. The bibshorts had seven thousand kilometres on them, and I didn’t want to take any risks with a new garment that might rub against me. The chamois ended up looking like cigarette paper, it was almost falling apart, but I didn’t feel any discomfort.

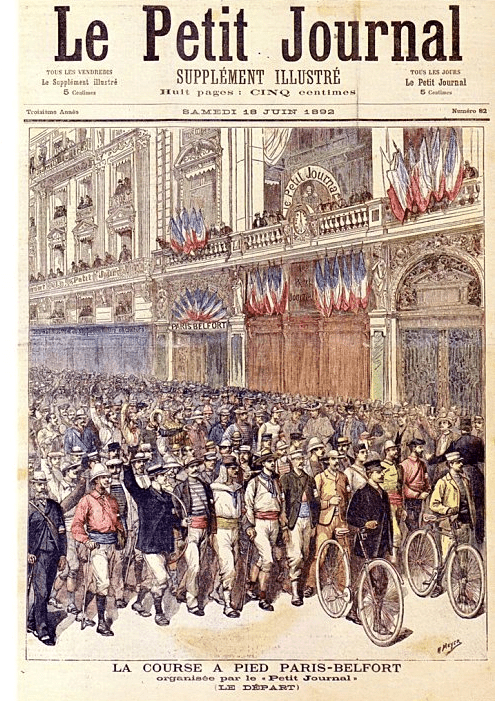

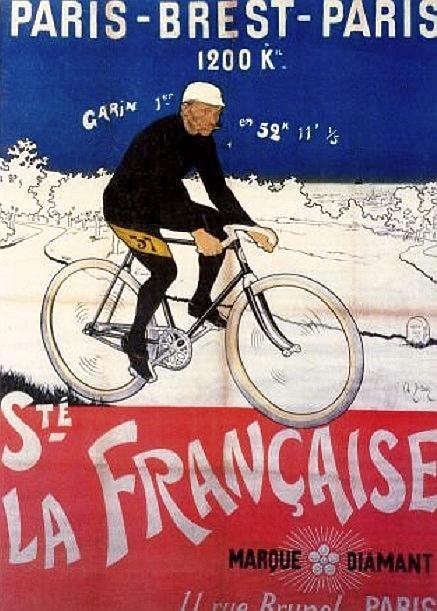

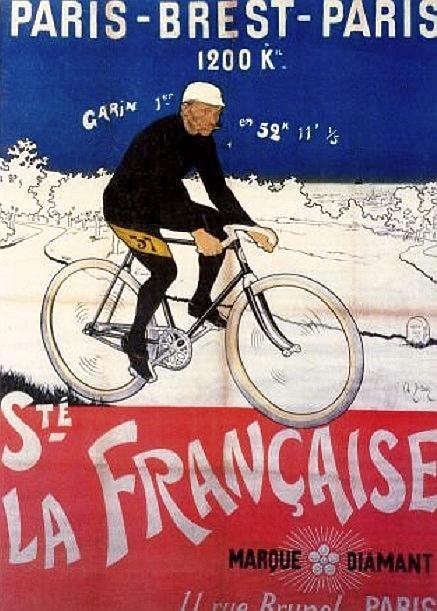

– I’d go to the North Basque Country and take roads I didn’t know, eat anything I could find, discover places… I like to go a bit further. Guisasola competed in cadets and juniors, but he discovered that his thing was the endless marches and in 1987 he signed up for the brevets: the approved routes of 200, 300, 400 and 600 kilometres that a cyclist must complete in a maximum time if he wants to enter the legendary Paris-Brest-Paris. The race was born as a professional race in 1891, so monstrous that it was only held every ten years, and the 1901 edition was won by Maurice Garin, who would become the first winner of the Tour de France in 1903. In the mid-20th century it became a randonnée (“walk, hike”) and is now held every four years. Some participants aim to complete it within the maximum time of ninety hours, sleeping some of the time, and others barely stop at the refreshment posts because they are chasing the best time.

Guisasola signed up for the 1987 race, felt good and left many people behind. He paid, of course, for the hazing:

– I got lost a couple of times at night. I took the wrong road for fifteen kilometres there and fifteen kilometres back. At that time, the regulations required us to carry mudguards and a dynamo headlight that would brush against you to give you light at night, it was useful to be seen but it didn’t give much light either, we were always riding on secondary roads with hundreds of junctions and it was easy to get lost. There were some arrows, but sometimes some bastard would turn them to send us somewhere else…

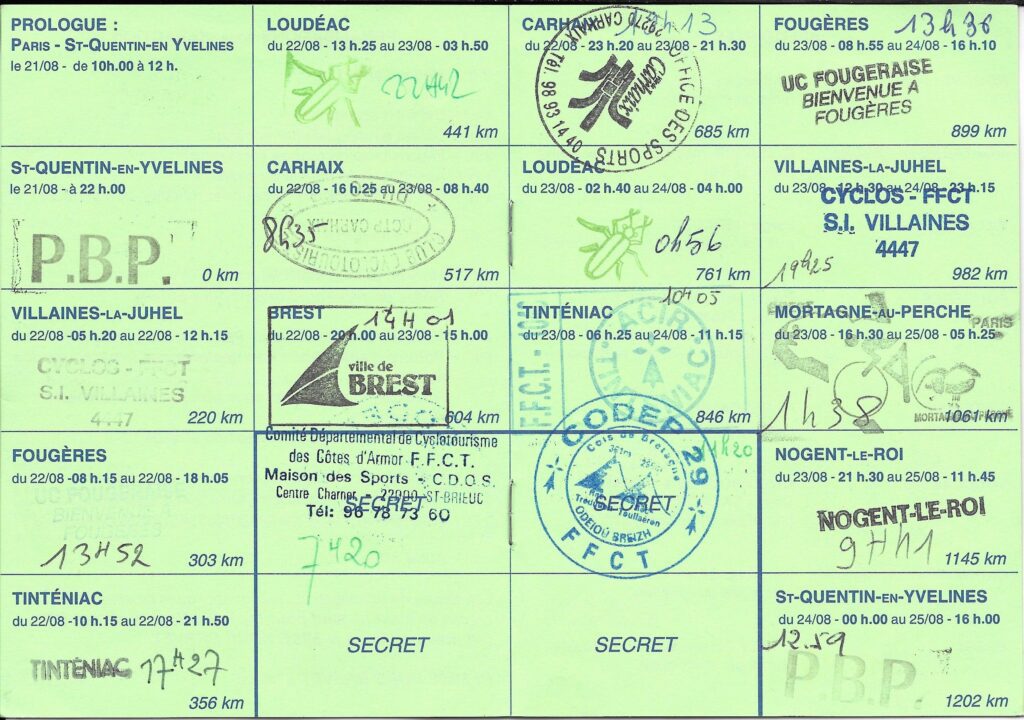

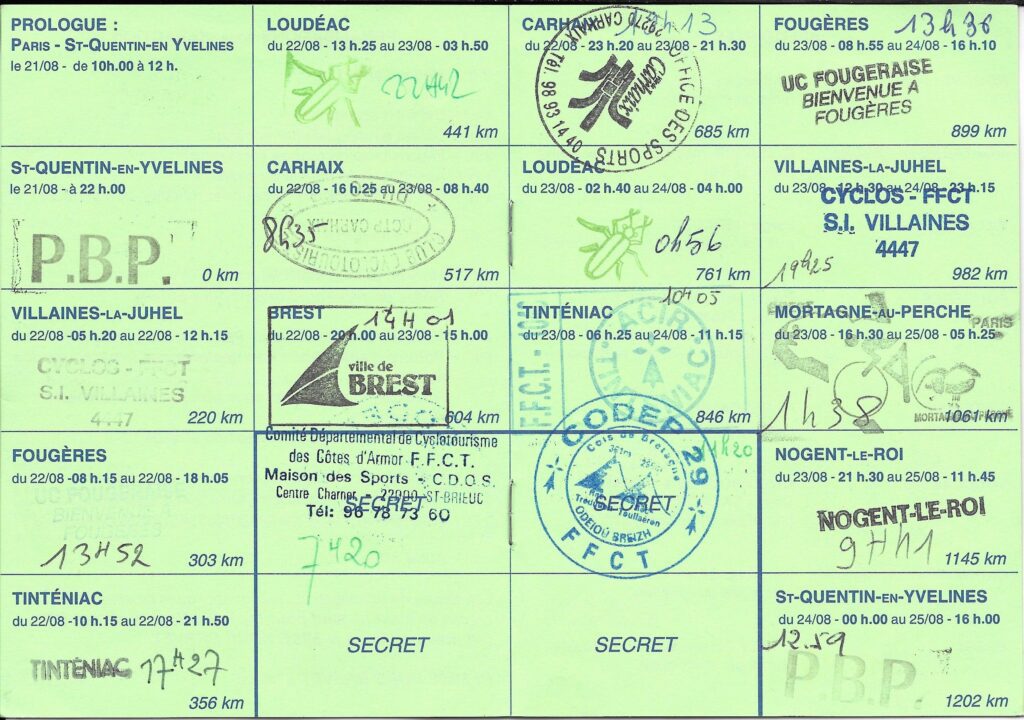

Every ninety to one hundred kilometres, the cyclists had checkpoints in cities that served as reference points. Only there could they receive food, drink and clothing from the cars accompanying them, and between these points they had to ride on different roads. With two hundred kilometres to go, Guisasola’s companions told him that he was being approached by the American Scott Dickson, one of the cyclists who has most often finished the race in less than fifty hours, the barrier that marks excellent times. Dickson had started six hours later than Guisasola, in the group of the fastest cyclists.

– I was riding with a French cyclist. We decided to slow down a bit to wait for Dickson, we saw a light at the end of the night and here came the guy, with a terrible stride, I don’t know, a 53×12 or something like that. He was riding up the hills sitting on the big chainring. He asked us for a relay, because he wanted to leave De Munck, the Belgian who had the best time until then and who was coming close. We helped him and we were the first to enter Paris: Dickson beat the record, 44 hours and one minute; the Frenchman and I did 50 hours and one minute.

Guisasola was a bit angry, because he was a minute away from that barrier that few cyclists surpass. But the experience helped him to improve in the following editions: knowledge of the terrain, training, nutrition?

– And the psychological part, which is key. You have very hard moments, moments of tiredness, weariness, you feel like throwing the bike away. But you learn that if you hold on for half an hour, your body turns around, it turns on and goes even better. Your physiology adapts, it’s amazing.

Guisasola had ridden in the Insalus-Danena youth team, the team of Jokin Mujika, Valentín Dorronsoro, Modesto Urrutibeazkoa, those who went on to the amateur and professional Orbea: the first cycling team that Etxeondo dressed. Guisasola knew Paco Rodrigo because they shared that world.

– When I finished my first Paris-Brest-Paris, Paco called me enthusiastically: “Alberto, come to Etxeondo”, we’re talking about when Etxeondo was still a farmhouse, “come and I’ll give you some bib shorts, when you’ve done so many kilometres and so many washes, bring them to me, we’ll see how they fit”… He did tests with me: instead of adding one layer of padding to the bib shorts, he added two, or an intermediate fabric to give them better cushioning…

For the next Paris-Brest-Paris, in 1991, Guisasola tested the Etxeondo bib shorts that the Banesto team was going to wear in that year’s Tour, the first one won by Induráin.

– They weren’t synthetic, at that time they were still made of suede. A very fine suede, a marvel, but you had to take good care of them. I didn’t use cream on them, because if you cover the pores of the leather you take away its breathability. I washed them and let them dry slowly, never in the sun, so that they wouldn’t stiffen. It was better to put on a slightly damp bum and massage it so that the leather would stay elastic.

The other garments were also important for so many hours of pedalling. Guisasola remembers the vest that was warm and didn’t get soaked, the rain boots, the first garments that Etxeondo manufactured with goretex membranes, which were waterproof, breathable and windproof…

– Until then, when it rained, we used to wear those transparent plastics that made you sweat in your own sweat and dehydrated you.

Guisasola wore the goretex garments before the ONCE cyclists.

Do you know what he did? Came with a can of reflective paint, He grabbed a paintbrush and started to paint some parts of the jersey.

– I was really hallucinating. María Jesús and Paco saw the possibility of experimenting with me in extreme conditions and they threw themselves into it. That was their spirit, to find the best solution to the most complicated problem. They made the garments to measure for me, the pattern, the cut, everything down to the last detail. In 1991 they opened the company in August, when they were on holiday, to finish my Paris-Brest-Paris clothes. I was amazed at all the attention. But I was just an amateur, a cyclotourist….

– They could use your publicity, a cyclist who cycles two days in a row and beats the Paris-Brest-Paris record wearing Etxeondo clothing…

– No way, I hardly ever appeared in the press. When I broke the record in 1995, I was interviewed by radio stations, newspapers, TV stations, but before that, almost nothing, I didn’t give Etxeondo any publicity. Paco didn’t care about that, he had Induráin, Perico, Kelly, the best teams in the world! What was I going to give him. He was driven by his desire to investigate, to experiment.

Guisasola remembers Paco Rodrigo’s efforts to get him a high-visibility jersey for the night sections.

– They didn’t make clothes like that back then. Do you know what he did? He came with a can of reflective paint, grabbed a paintbrush and started to apply the paint to some parts of the jersey, to see how it looked, how the elasticity of the garment responded, what happened after washing it… He was enthusiastic about all these experiments. And they motivated me: he gave so much of himself for me that I had to do my best, I couldn’t give up at the drop of a hat.

For his second participation, in 1991, Guisasola prepared himself thoroughly. He never stopped working in his medical practice, so he took advantage of Wednesday afternoons to ride three hundred kilometres until the early hours of the morning and at weekends to complete runs of five hundred kilometres. Four days before Paris-Brest-Paris he wanted to go out on a sunny terrace in Artajona (Navarre), didn’t see the transparent window, went through it and it exploded all over his body. He was taken wrapped in towels to the hospital, where they removed a thousand shards of glass and sewed up his legs, arms and tongue.

– I had been preparing for the test for four years and a few days before that happened to me… I didn’t want to give up. I had to give it my best shot. The next day I cycled from Artajona to San Sebastian, all stitched up and full of bandages. I thought that if I did those 150 kilometres, I could do a few more.

And he did. He completed the Paris-Brest-Paris, in the last stretches he slacked off due to discomfort and accumulated fatigue, he couldn’t keep up with the group he was cycling with, but he still improved his record: 48 hours and 38 minutes.

– I finished tired but with a good feeling. Despite the stitches, I was quite comfortable. The clothes helped a lot: when I finished I didn’t have that need to take my shorts off as soon as possible because I couldn’t stand them any more, I didn’t have any chafing or wounds or anything. Everyone gets some sore areas, but the perineum from the pressure of the saddle for so many hours, the wrists from the pressure of the handlebars, that’s hopeless. As for the rest, that year the clothes were very important to avoid any discomfort.

In his third participation, in 1995, Guisasola broke the race record. Thanks to the favourable wind, the first cyclists completed the 620 kilometres of the first leg in just nineteen hours. On the way back, they organised themselves against the wind.

– With 400 kilometres to go, there were nine of us in the lead. We calculated that if we stayed together until the end, in relays, we could get the record. In the last couple of hundred kilometres we averaged 34 or 35 km/h. It’s incredible how the body responds when you train it, when it’s well fed and well hydrated: after a thousand kilometres, you can do two hundred at the same pace as if you were starting from scratch.

The nine riders (six French, two Americans and Guisasola) entered Paris together and set a time of 43 hours and 20 minutes. Only eight riders from the 2015 edition have beaten that time, led by Bjorn Lenhard with 42 hours and 26 minutes.

Guisasola has not taken part in Paris-Brest-Paris again but at 62 years of age he says he is young and has opportunities ahead of him to repeat it. If he hasn’t already repeated it in so many circumstances in life:

– For me, Paris-Brest-Paris helps me every day. In the end, you train your ability to overcome, to endure the bad moments, to make yourself strong. That helps you in the hard moments of life. And it’s funny: I still have dreams in which I cycle to Paris.