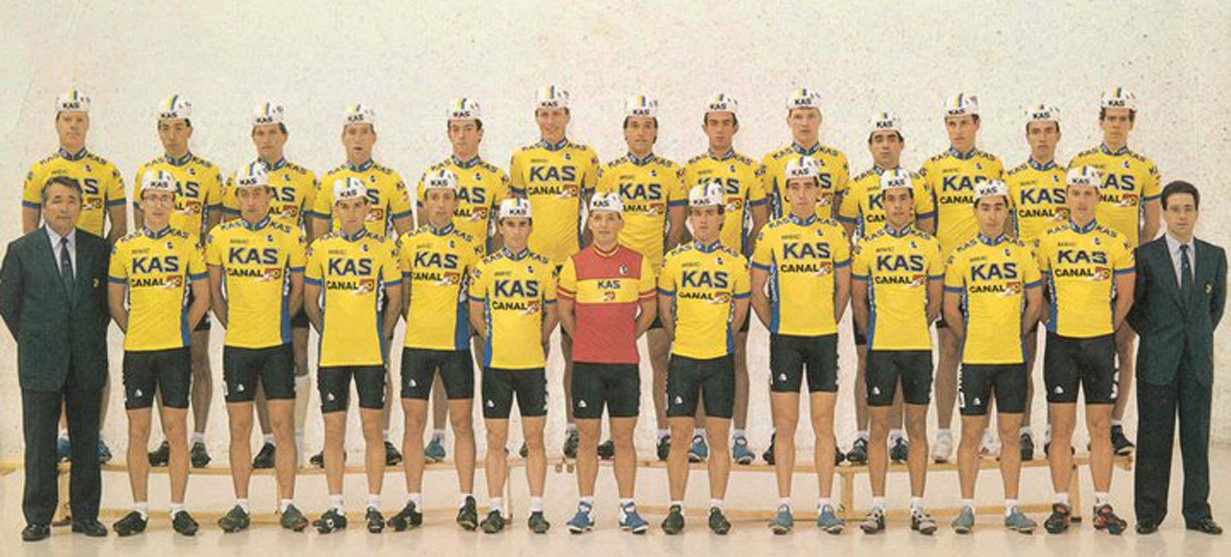

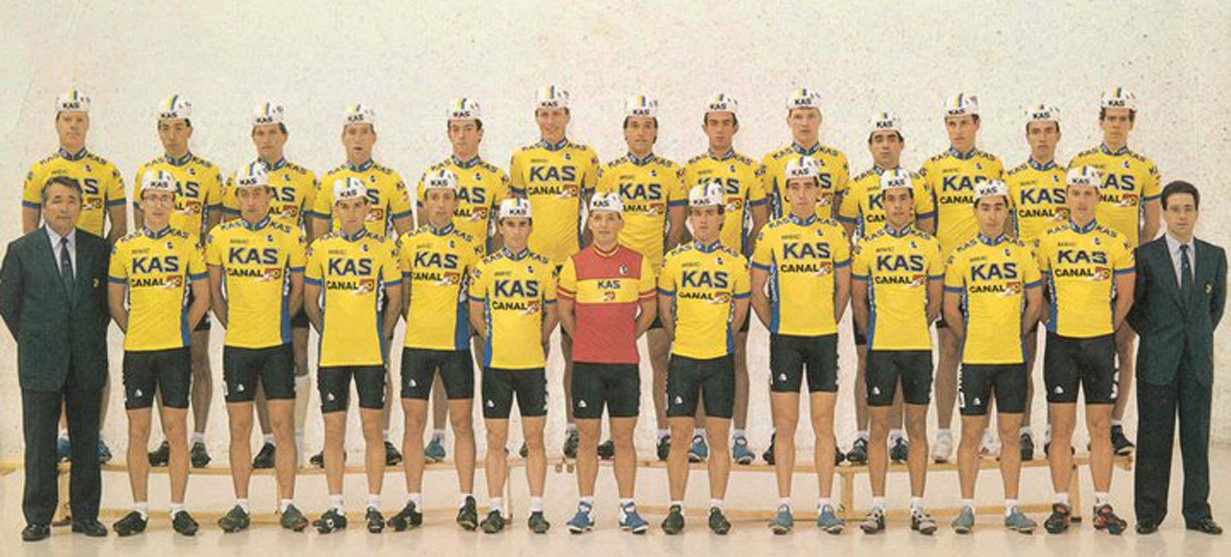

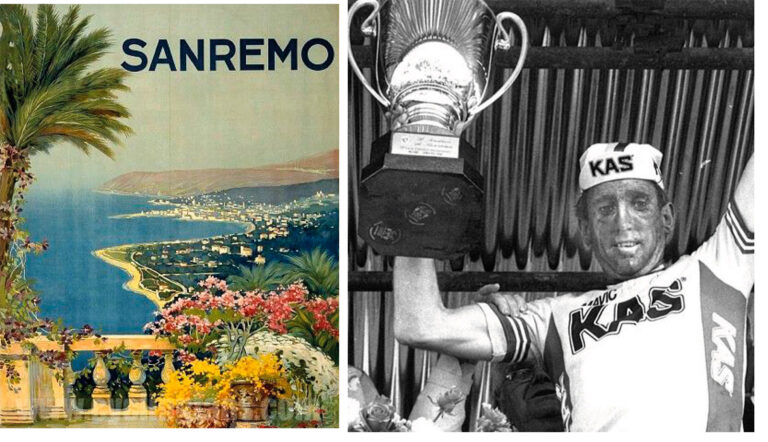

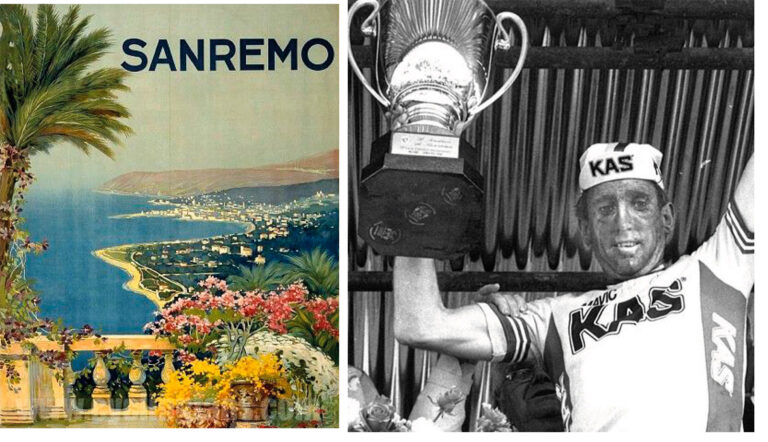

Soft drinks company Kas, title sponsor of a legendary cycling team in the 1960s and 70s, decided to return to the peloton in the mid-80s with an ambitious new project. They made a marquee signing in the Irishman Sean Kelly, hired Ramón Mendiburu as manager and ordered their clothing from Etxeondo.

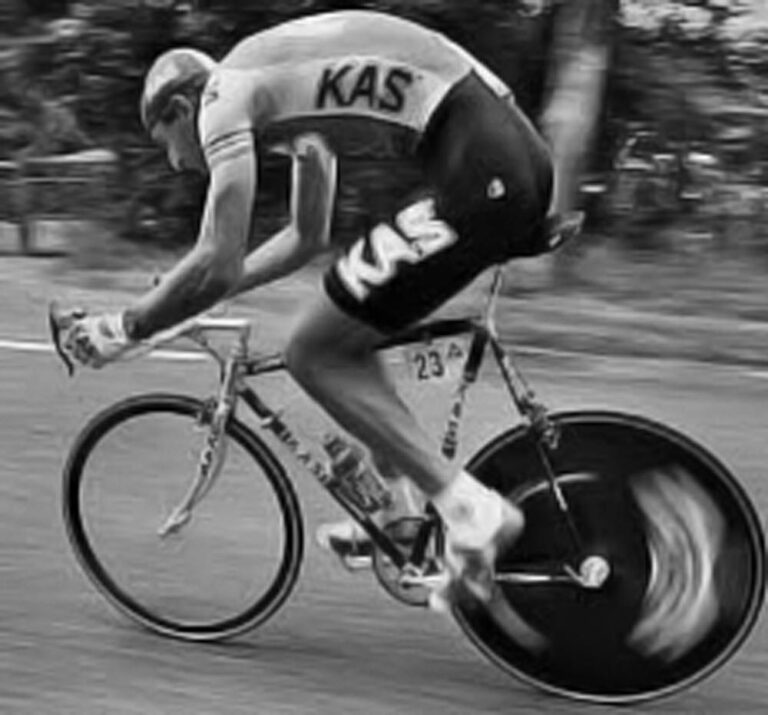

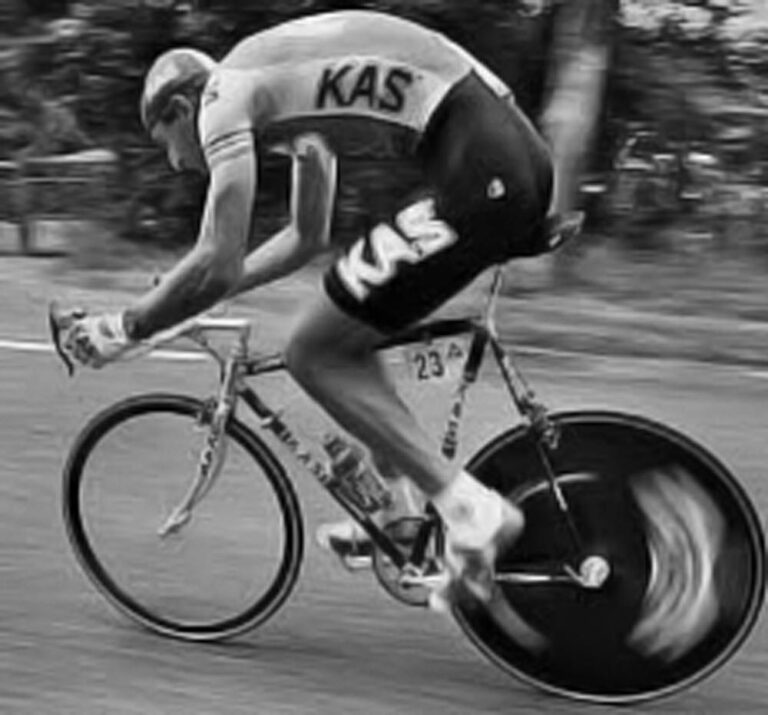

They also chose a jersey design very similar to the classic Kas; yellow jersey with black lettering on the chest and narrow blue stripes on the collar, sleeves and sides. For the Tour, which had long prohibited yellow jerseys on the basis they could be confused with that of the leader, Kas inverted the colours: a blue jersey and small yellow stripes. Paco Rodrigo was loath to give up the identifying image of the team in the most important race in the world. So in 1988 he dared a little heresy.

-Paco’s ideas,” laughs Mendiburu. “He goes and sends us a jersey for the Tour that is more yellow than blue…

-It was 50/50, so I left it late before showing it to anyone, timed it so they couldn’t tell us it was a yellow jersey. It had a yellow chest and back, but the shoulders, sleeves, and side were completely blue. You saw the rider go by and you saw the blue, it couldn’t be confused with the yellow jersey. -Well, Goddet, the director of the Tour, came and told us: ‘You don’t go out with that jersey’. -Goddet was from the old school, director of the Tour since the 1930s. -“I went to speak with Xavier Louy, who later that year took over from Goddet,” Mendiburu continues. “And he told me nothing, never mind, that we go out with that jersey.” -“I had absolute confidence in Ramón, I knew that they weren’t going to give us any trouble with him in charge,” Paco smiles.-Paco’s ideas,” laughs Mendiburu. “He goes and sends us a jersey for the Tour that is more yellow than blue…

-It was 50/50, so I left it late before showing it to anyone, timed it so they couldn’t tell us it was a yellow jersey. It had a yellow chest and back, but the shoulders, sleeves, and side were completely blue. You saw the rider go by and you saw the blue, it couldn’t be confused with the yellow jersey. -Well, Goddet, the director of the Tour, came and told us: ‘You don’t go out with that jersey’. -Goddet was from the old school, director of the Tour since the 1930s. -“I went to speak with Xavier Louy, who later that year took over from Goddet,” Mendiburu continues. “And he told me nothing, never mind, that we go out with that jersey.” -“I had absolute confidence in Ramón, I knew that they weren’t going to give us any trouble with him in charge,” Paco smiles. From time to time, Etxeondo had to juggle changing the design of the jerseys, due race organisers or teams landing last-minute sponsors. -“I had to make jerseys to go to the Tour with a new sponsor in two or three days,” says Paco. “Design the clothes, produce them, ship them, all against the clock.“Some sponsors did have a corporate image worked out, but others simply sent you the logo and I had to invent the rest. “Seur, for example, had a very clear and beautiful idea, but of course, then you also have to win races. “If you make a beautiful jersey but the cyclists don’t win, it still doesn’t look good on you. “The famous La Vie Claire jersey was magnificent, yes, but it got the fame it did because Hinault and Lemond wore it and they won Tours.” The La Vie Claire jersey was inspired by Mondrian’s paintings: rectangles of blue, red, yellow, white and black, separated by thick black lines. -“Less is more and some find it hard to understand that,” says Paco. “You make them a sober, elegant design, and they tell you to put the logo in more places and to put words in the free spaces. “They think the more you fill the jersey with advertising, the more it will be seen. “And it’s not true. The jersey drowns you, they fill the spaces where the design breathes. “Sometimes I have accepted, sometimes we have negotiated, sometimes I have refused. “I want my jersey to be elegant and look good. “I understand there are teams that get 17 sponsors and you have to get them all on the jersey, but I’m not willing to do just anything. “It’s my image, it’s an Etxeondo jersey, it can’t be just any mess.“There are jerseys that I wouldn’t do even if the best team in the world came offering me a fortune.”

“SURGENT TENDERLOIN FOR KELLY”.

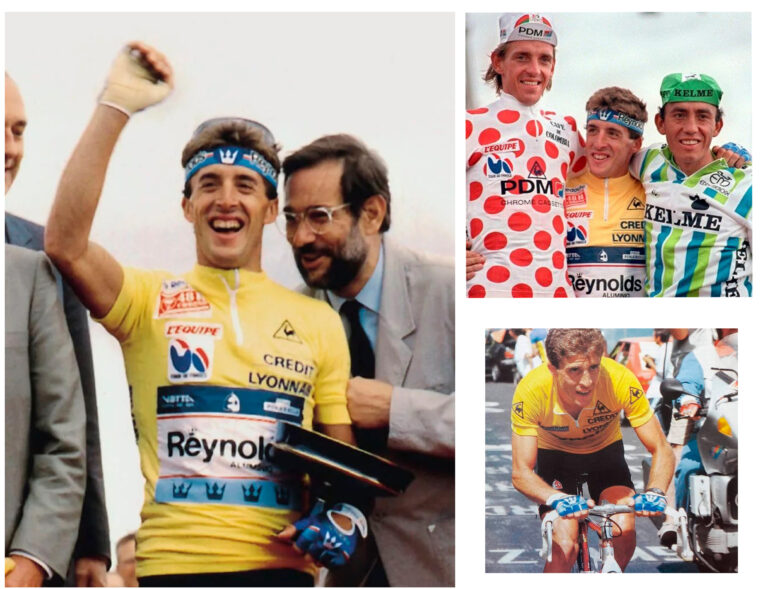

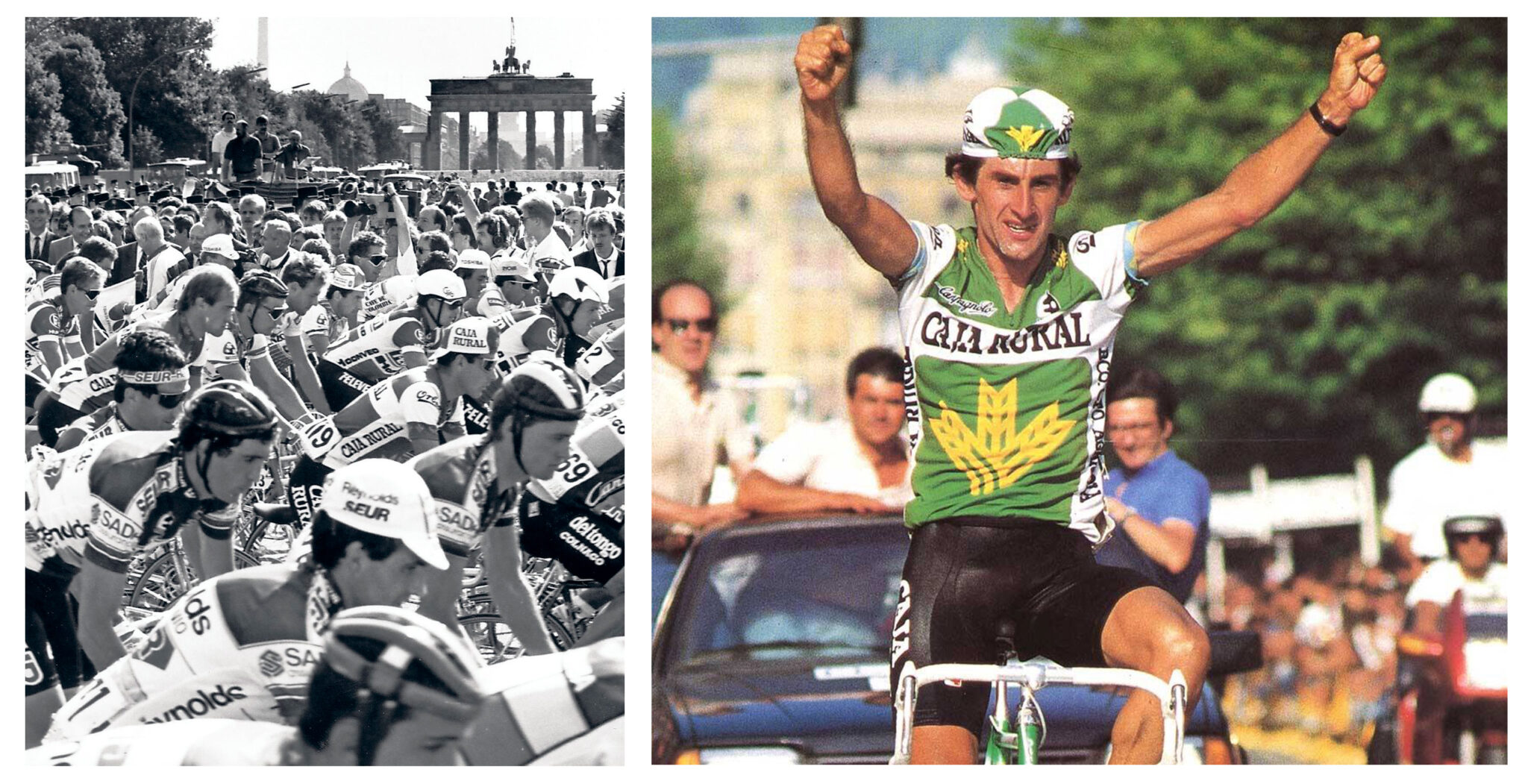

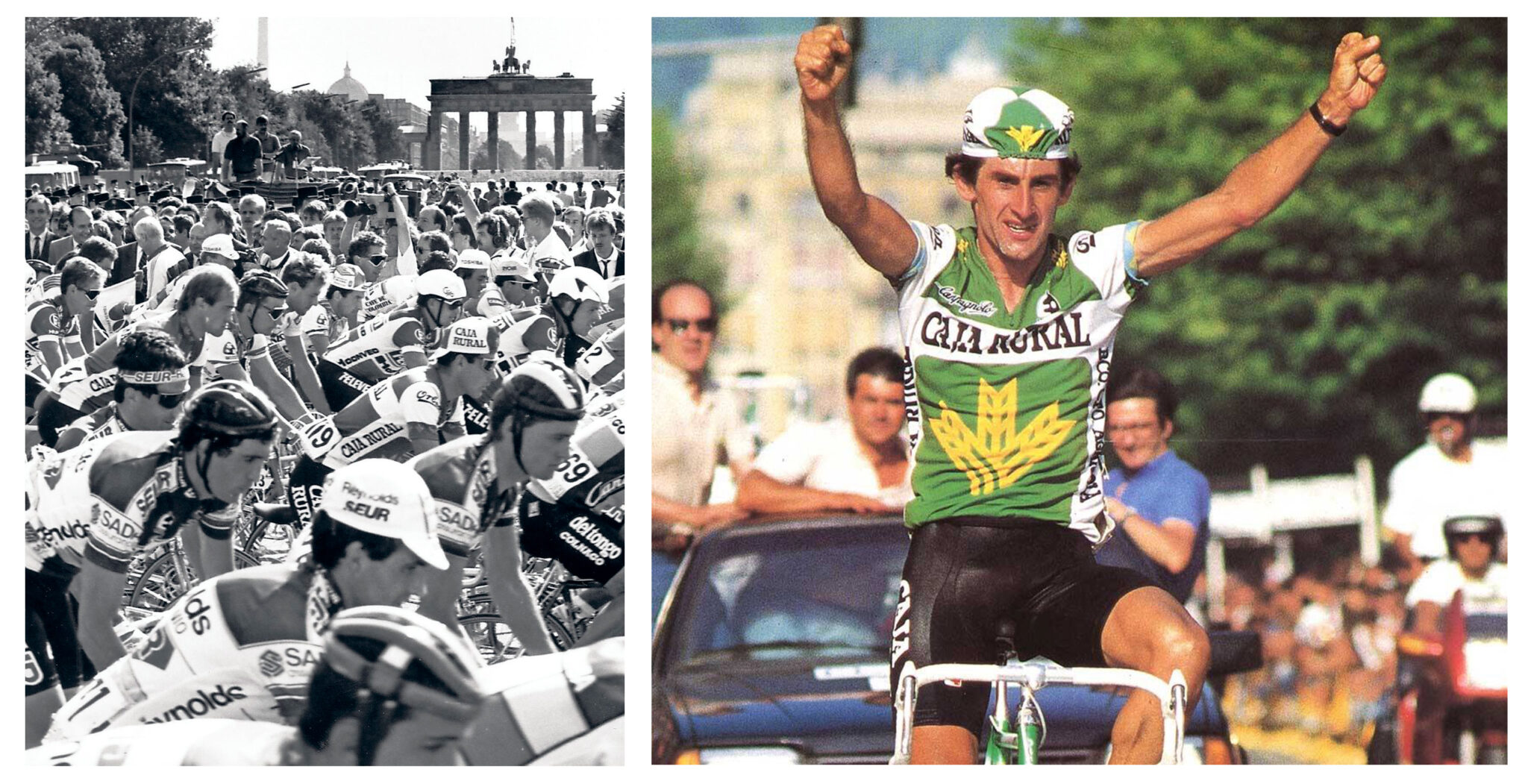

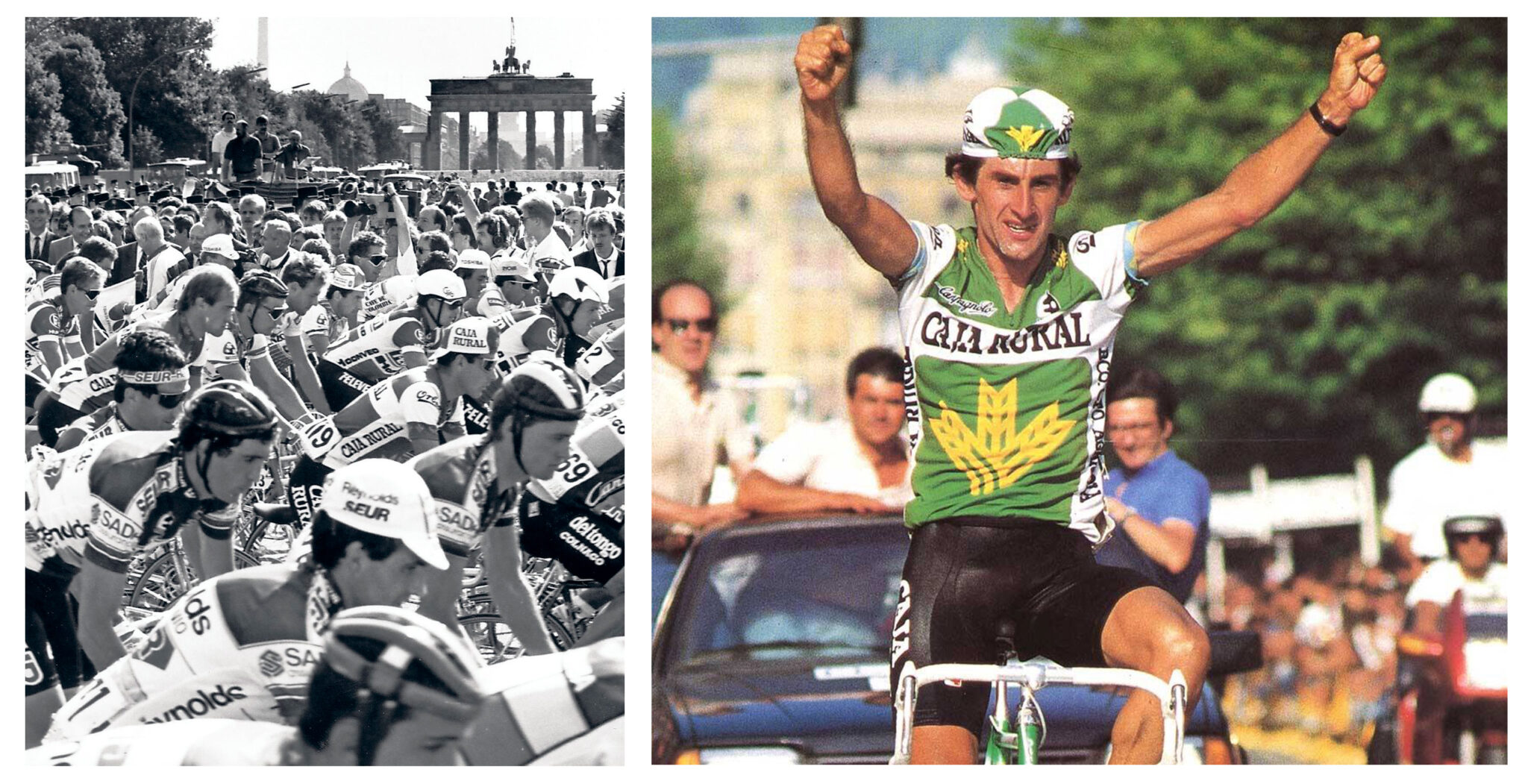

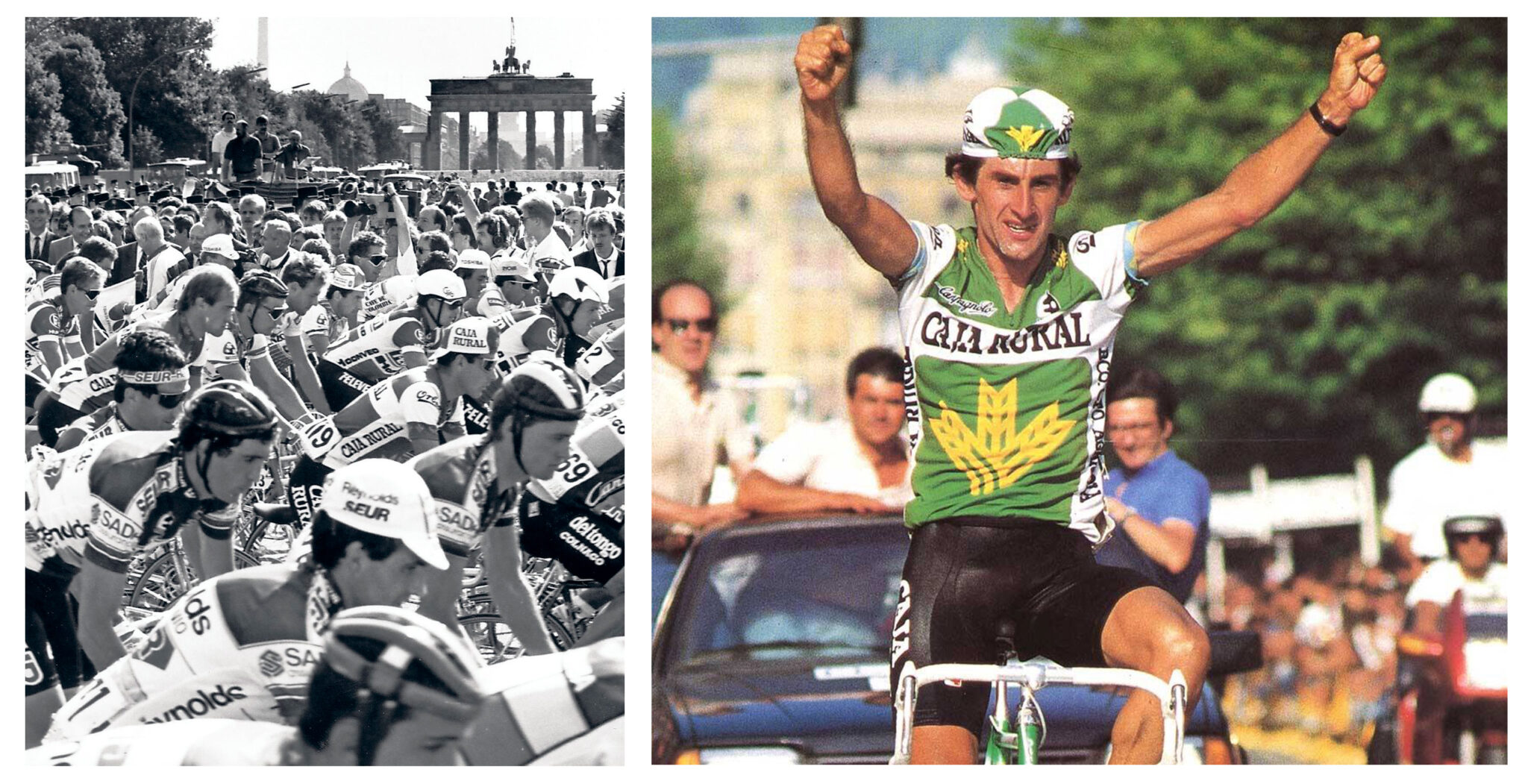

In 1986, four teams rode the Tour in Etxeondo clothing: Orbea, Fagor, Kas and Reynolds, two based in Gipuzkoa, another in Álava and another in Navarra.

-“Marketing has changed; back then the most important thing was to dress professional teams and win races,” says Paco Rodrigo.“Here we had everything; good riders, good companies with an interest in investing in cycling and signing big names. “We had a lot of cyclists winning races, it was impossible to even keep count. “I remember Jean-Luc Vandenbroucke, who rode for Kas. “At first I didn’t even know who he was, but the guy started winning a lot of time trials, he even wore yellow after winning the prologue of the Vuelta.”

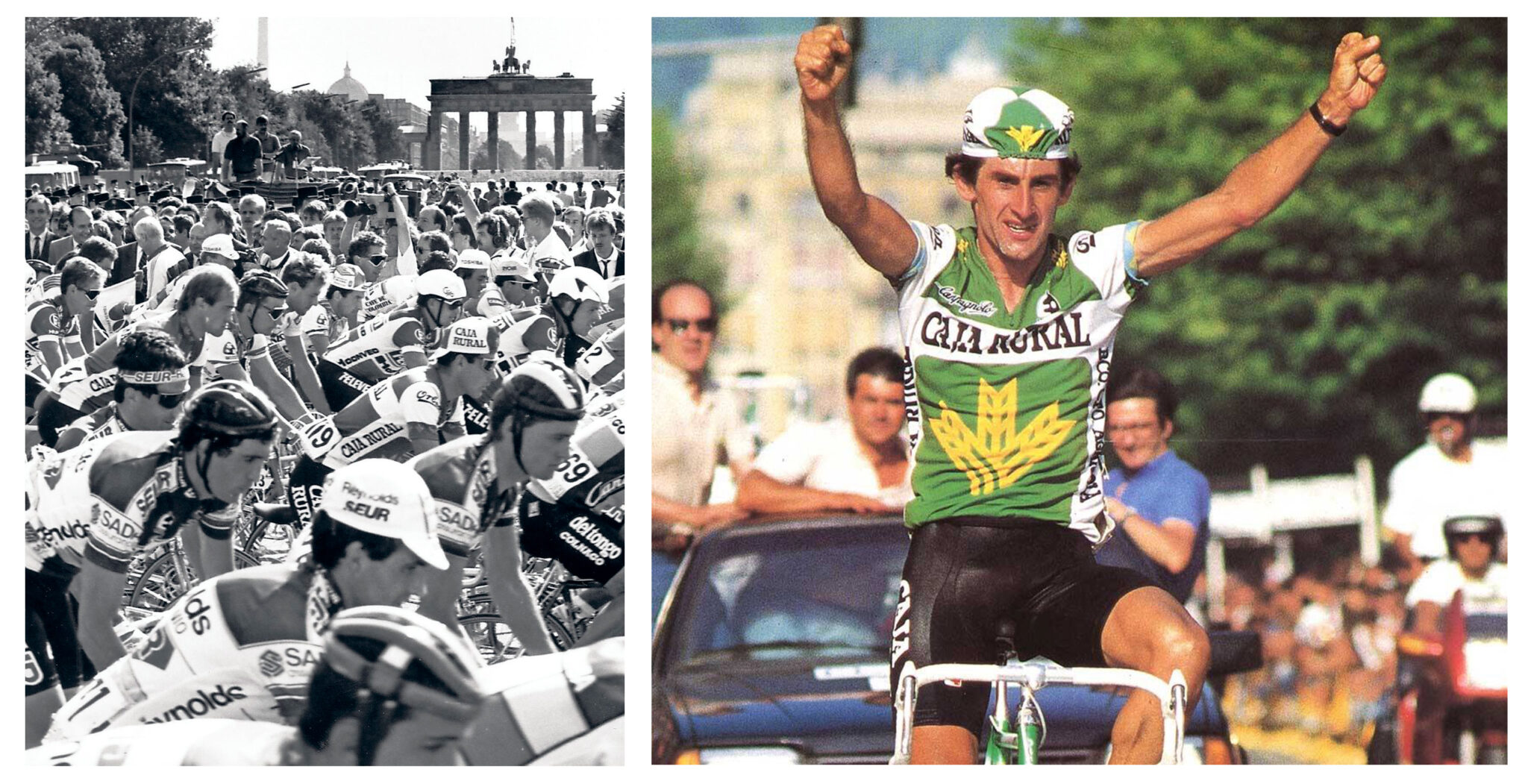

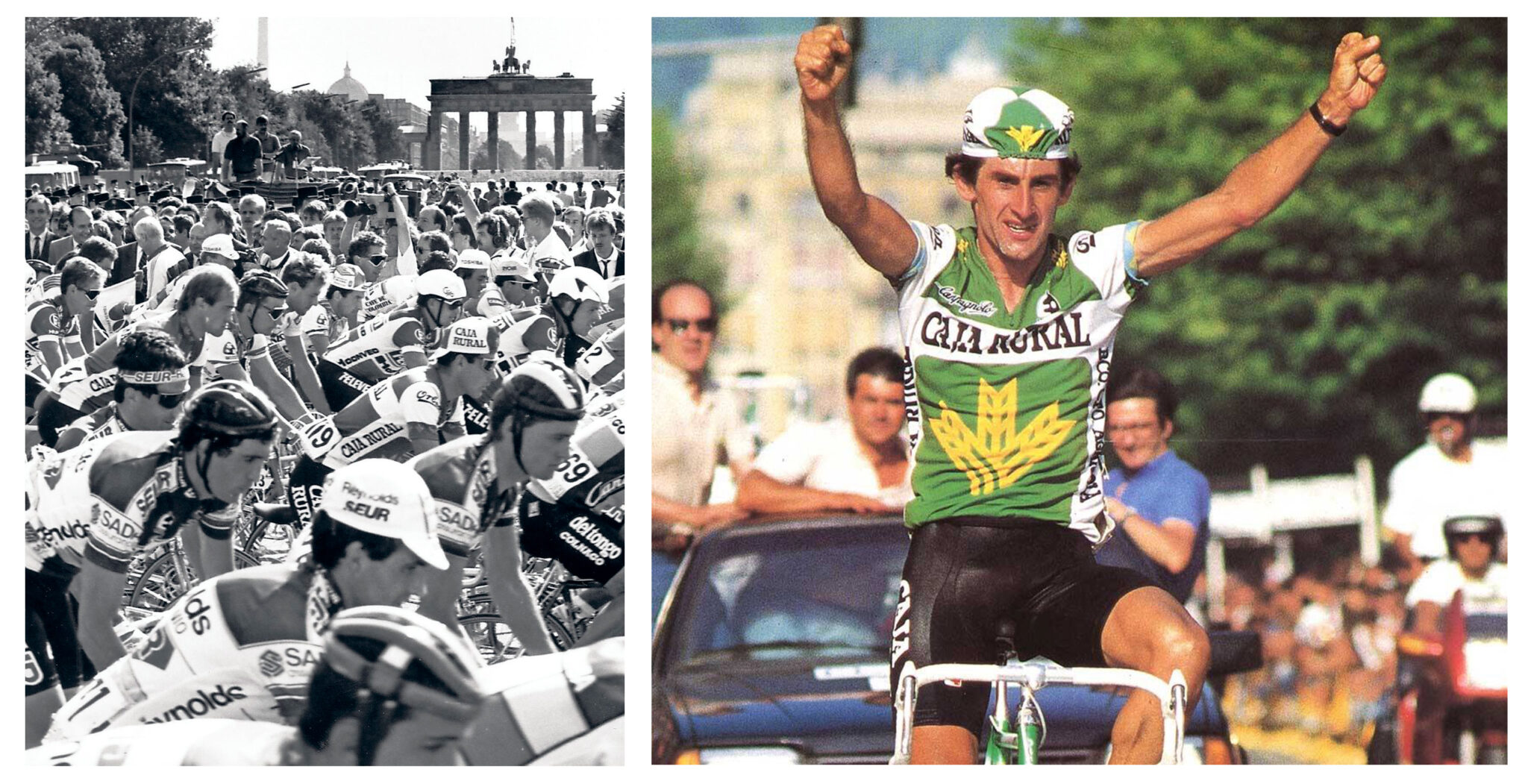

In 1988, Etxeondo won the Tour with Delgado and the Vuelta with Kelly. The victories did not come easily: Paco had to spend many hours working on the Irishman’s shorts, because he frequently suffered sores. The previous year he had withdrawn from the Vuelta when he was the leader with four stages to go, because he could no longer stand the friction with the saddle.

That night, the Vuelta doctors opened the infected area to clean it of pus and reduce the inflammation, but it was not enough.

-“If a rider came to me with a problem, I put in the hours it took until I found a solution, it didn’t matter if he was a leader or a domestique,” says Paco. “The shorts are very delicate. Any imperfection can ruin a race. “Everyone has their problems; some wanted very wide chamois they didn’t really need and I had to convince them this was not the solution. “But it is a very personal matter. Each cyclist must be given what they need and that is a lot of work.

-“Imagine the year we had four teams on the Tour. “We had to fine tune the shorts of 40 riders for the most important test of the year, so that none of them had any problems across three weeks.”

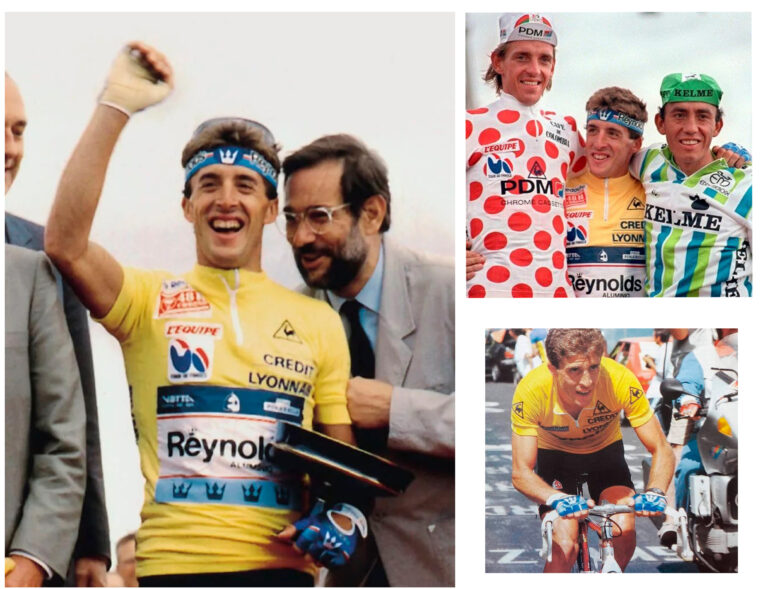

-“I remember an International Critérium,” says Paco Rodrigo. “In the morning stage, Kelly finished with a group of five or six – Roche, Fignon, Bernard – the best of the best, and beat them in the sprint. “They were giving him a massage in the car and he told Mendiburu: ‘Don’t worry, I’ve saved my strength for this afternoon’s time trial, you’ll see’. “That confidence impressed me. Look what rivals he had, huh? But he had it very clear, he knew that he was going to beat them and he beat them. That one came out with an iron nerve.”

“He was very professional,” confirms Mendiburu. “A quiet, humble, very attentive guy.”

In 1988, the season in which the winners of the Tour and Vuelta wore Etxeondo, the Giro d’Italia experienced its most dramatic episode: the snowfall on the Gavia. Even now, Pedro Delgado, 10th in that freezing hell, does not believe the clothes of the time were insufficient. The problem was the extreme conditions, which would have seen the stage cancelled today: They rode over the Gavia at 2,621 metres in five degrees below zero with snow covering the road and began a descent of 25 kilometres in an effective temperature of around 30 below zero.

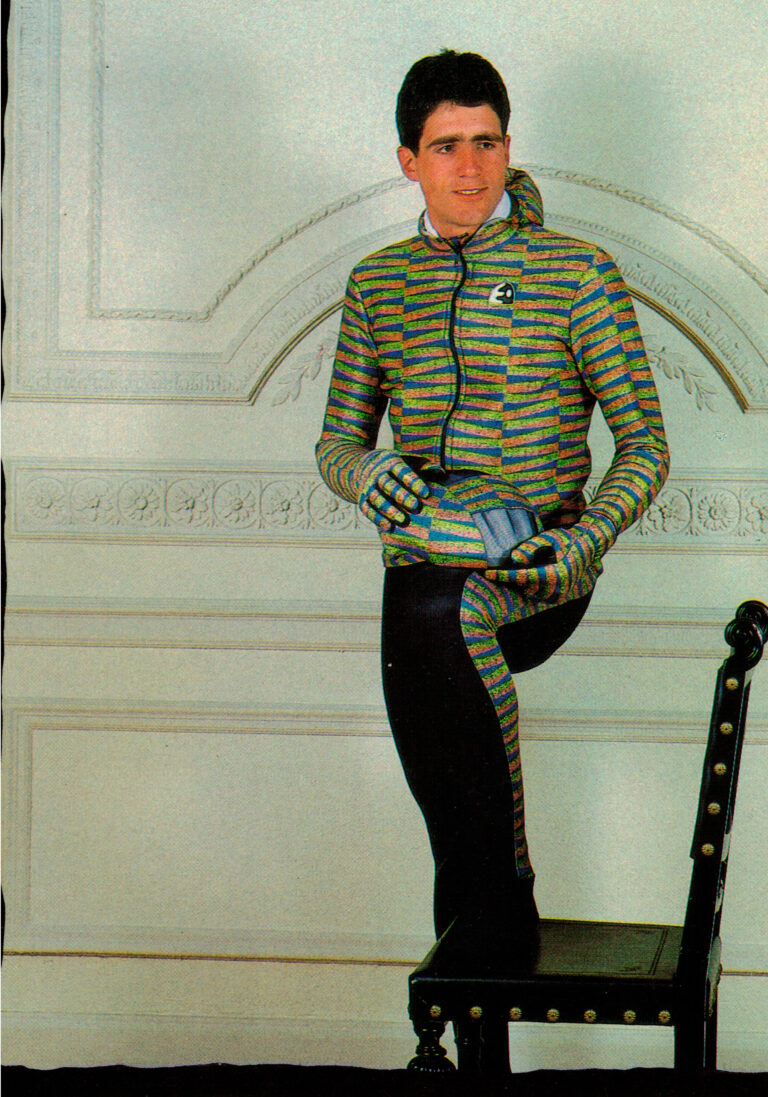

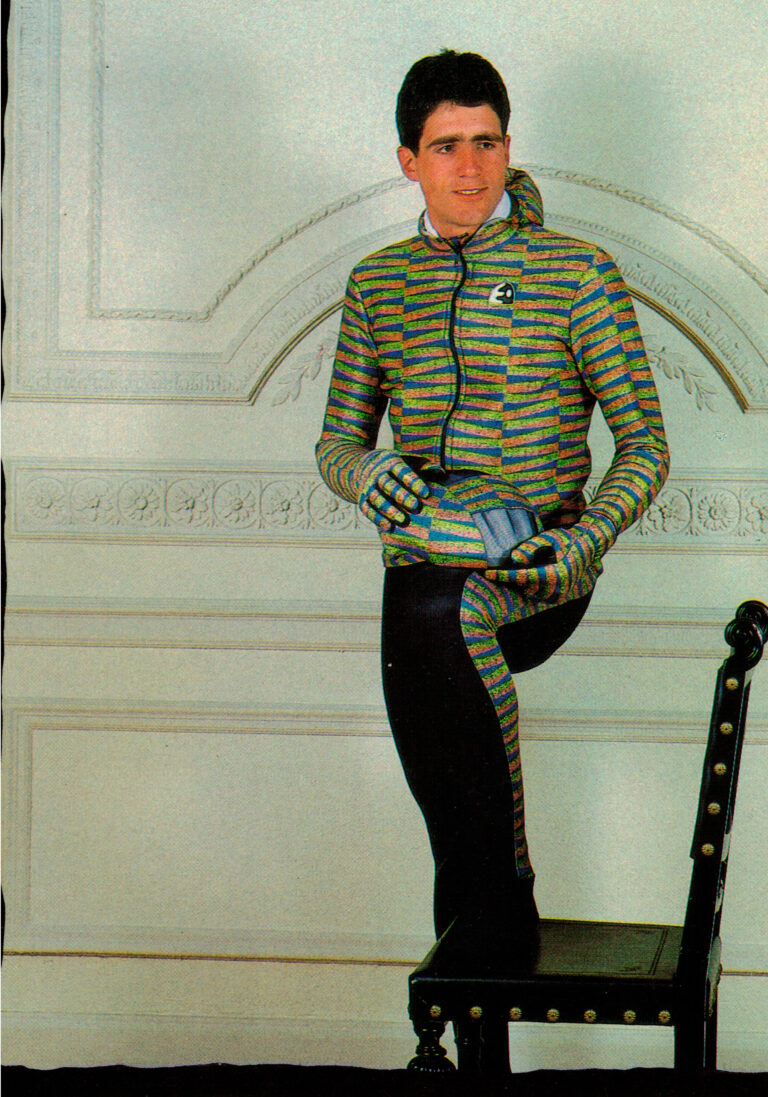

-“We already knew it would snow before the race,” says Delgado. “In fact, in the first kilometres of the stage there was talk in the peloton of stopping, but we carried on. “I started to climb the Gavia wearing neoprene gloves, which were a new innovation, and very good, but they made me too hot and I put them in my pocket. “Near the top, I got colder and colder. By the summit, I was shivering. “I stopped by the side of the road and the Reynolds staff gave me a bottle of hot tea and one of those thermal jackets with a hood that Etxeondo made, which were very good. “I tried to put on the gloves, but I couldn’t anymore, because my hands were so cold I couldn’t feel my fingers. “So I rode down the mountain without gloves; I don’t even know how I managed to brake in the corners. “At the time, we already had good, warm clothes.“There were neoprene and thermal garments, but it was impossible to prepare for conditions like that. “That day, we learned it is better if the staff wait for you with bigger-than-normal gloves in that weather, so that you can put your cold hands straight in.“It was not a normal situation.”

-“By that time, we already made shorts and undershirts that were warm,” explains Paco Rodrigo. “We used a special hollow fibre fabric, a real advance in thermoregulation. “I always made friends with textile engineers; I met the only ones who manufactured those fibres and bought them from them. “Then they stopped making them; they dismantled the machines, and I had to assemble them myself to continue production. “We also used water-repellent fabrics, we sold a lot of clothing for riding in the cold and rain. “We were always attentive to technical advances.”

As Etxeondo expanded on to the international stage, Paco Rodrigo opened a workshop in Castejón, his hometown in Ribera Navarra. About 10 people made clothing in the workshop, with a few others self-employed, sewing at home.

-“They brought my work to my home,” recalls Amparo Martí, who has been making Etxeondo garments for 36 years. “I started sewing Kas caps and Reynolds gloves. It was good for me to work at home, because I had two little girls, and a few years later we all went to the workshop.” Now 30 women work there, making all the clothing for the professional teams and all the Etxeondo shorts. -“The shorts are our specialty, the star product,” says Martí. “At the beginning, we had a lot to learn, because lycra is a complicated fabric, very elastic, it opens, it tears. “With the first machines we used, the lycra would break, so they bought other, more specific machines. “And then there is the chamois: it is very delicate, if you put it half an inch out of place, you can ruin a cyclist’s race. “Seamstresses start working here and spend three or four months learning how to place the pads before sewing the first one. “They always tell us: we do not pay for the quantity of garments sewn, but for the quality.”

Martí is 65 years old and close to retirement. She says she will be very sad to leave the workshop.

-“It’s my life,” she says. “We have worked so hard and we have been so excited to see the results. “We are always attentive to the races, we see the cyclists with our clothes on TV and we comment on it: ‘Hey, have you seen how good the zippers are, how good the skinsuit looks…’. “That is very important in life: the pride of doing things well.”